And what sort of harmony is it, if there is a hell? I want to forgive. I want to embrace. I don’t want any more suffering. And if the sufferings of children go up to make up the sum of sufferings which is necessary for the purchase of truth, then I say beforehand that the entire truth is not worth such a price. I do not want a mother to embrace the torturer who had her child torn to pieces by dogs. She has no right to forgive him. And if that is so, if she has no right to forgive him, what becomes of harmony? I don’t want harmony. I don’t want it out of the love I bear to mankind. I want to remain with my suffering unavenged. Besides, too high a price has been place on harmony. We cannot afford to pay so much for admission. And indeed, if I am an honest man, I’m bound to hand it back as soon as possible. This I am doing. It is not God that I do not accept, Alyosha. I merely more respectfully return him the ticket. I accept God, understand that, but I cannot accept the world he has made.

Ivan Karamazov, in The Brothers Karamazov by Fyodor Dostoevsky

Religious deconstruction has been one of the big buzzwords in Christian media over the last few years. The idea of taking apart your faith, especially a faith full of damaging, difficult, or confusing ideas, ideas that when held up against modern science and social norms and knowledge seem less and less defensible every day, is an enticing one for Christians all across the denominational and ideological spectrum. Books and podcasts and TheoEd talks and all variety of media have been produced to appeal to the deconstructing crowd, helping numerous folks find a new idea of Christianity that works for them, or to leave it behind all together.

Of course, this has also spawned a mirror image media explosion, of still-committed Christians (largely conservative and evangelical) who see the rise of deconstruction as an attack on faith, a buzzy idea hiding the spectre of postmodernism and atheism. This has also led to books and podcasts and megachurch sermons, all of them deconstructing deconstruction, if you will.

I deconstructed my faith, in the early and mid-2010s. In college, as I studied political science, became involved in electoral work and activist causes, and dove into philosophy and academics, the major claims of Christianity – especially the miraculous and bizarre – no longer made sense. Pairing that with a social impact that seemed largely negative and regressive made Christianity deeply unappealing. But I could never shake that intuition I had that God was real, somehow, and the longing for return to the ground of all being never left me. I found church settings and friends who helped me strip away so much of the accoutrement of faith, drilling down towards the words of Jesus and their ethical impact on the world.

I like to say today that I’ve largely reconstructed faith. The edifice of orthodox Christianity makes sense to me, and I no longer reject the Trinity, the miracles, the Resurrection, or concepts like salvation, justification, or atonement. This isn’t to say I’ve returned to the faith I held 15 years ago. What I did do was take it all apart, look it all over, and put it back together, in a way that largely resembles the piece it was before, but with some new movements inside it that help it make sense of the way I see and experience and think about the world. All of my past – the faith I grew up with, the years of agnosticism at best, the political schooling and commitments I developed, the deconstruction, the academic dive into theology, the critical voice, the reconstruction – all of it informs and animates the faith I hold on to today. Deconstruction was not an endpoint, nor was it a theological death sentence. For me – and this is just for me – it was a necessary way station on the path to understanding who Jesus was and why he lived and died and anyone cared.

I’m getting a little far afield from what this essay is about, so let me pull us back towards the current. Recently, popular evangelical voices Alisa Childers and Tim Barnett released the book The Deconstruction of Christianity: What It Is, Why Its Destructive, and How to Respond. Childers and Barnett are both former deconstructors themselves, and you can find both of their stories out on the internet in a variety of places. I have not read the book yet, but I’ve read several reviews, a variety of interviews and pieces by the authors, and listened to them speak about it. This isn’t a book review and I’m not really interested in trying to evaluate their claims specifically; my point in bringing them up is to point out that deconstruction is a hot button issue in popular Christianity, all across the spectrum. For a while, the dominant strain about it was positive: a lot of stories about deconstructors and their experiences. Recently, the backlash in more conservative places has started to supplant that positive reception, and you see a lot of apologetics that frame their work as a response to deconstruction. Rarely are these defenses of the Christian message per se; more often, they are point-by-point critiques of deconstruction stories, or even more common, “How-To”-style pieces for those who know and love someone going through deconstruction.

One last point on this debate: one piece I read by Childers was an article at The Gospel Coalition, titled “Help! My Loved One is Deconstructing.” The piece provides five statements defining who deconstructors are, and the fifth one is “Deconstructors are Rebels.” Here is what Childers writes: “For many, deconstruction is about self-rule. They refuse to bow their knees to the sovereign Lord. No one, including God, gets to tell them what to believe or how to live.”

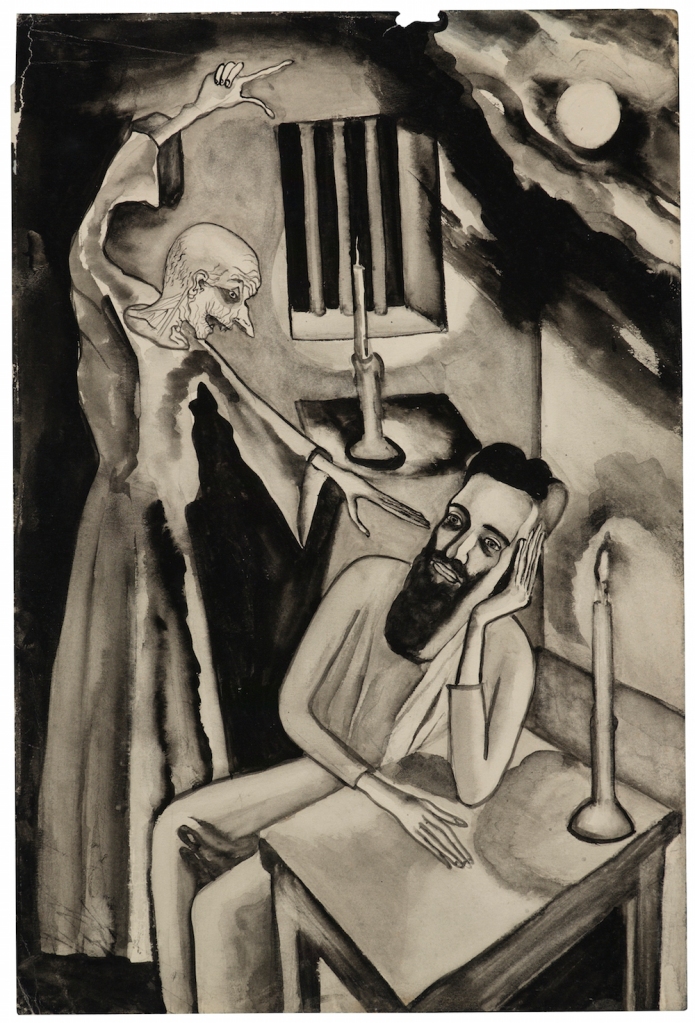

Ivan Karamazov was a rebel in this vein, although to call him a deconstructor would probably be too mild a phrase to use. Ivan rejects that sovereign God, not from disbelief, but because of his deeply held sense of compassion for those who suffer in this world. In the passage that opens this essay, Ivan speaks to his younger brother Alyosha after witnessing a serf child being killed by dogs at the direction of his master, after the child accidentally harmed one of his master’s dogs. Ivan (and perhaps all of us) cannot conceive of a good God who made a good world in which children are tortured and killed by a fellow human being.

Perhaps you feel this way looking at the crisis in Gaza. One does not have to take a political position on the status of Israel and Palestine to be struck by the horror of the knowledge that, in almost five months of warfare, over 12,000 children have died, or that many thousands more are actively starving. Where is God in this?

I started this essay with a touch on the deconstruction issue because critiques of deconstructors like those levied by Childers and Barnett fail to take into account the Ivans of the world. For instance, this is how megachurch pastor and author John MacArthur describes deconstructing in a sermon: “What I hear is this, and I read many of these testimonies this week: “I had a bad experience at church.” It all comes down to experience. It all comes down to what everything comes down to in this culture, and that’s “me,” that’s “me.”” Macarthur’s sermon is long and theologically dense and Scripturally informed. But it is, at its core, unserious, just like I feel sure that Childers and Barnett’s book is also unserious. The anti-deconstruction crowd seems to think all those deconstructing are just ignoring the “obvious” truths about God and Jesus that they seem to have such a firm grasp on. But how would they explain 12,000 dead children in Gaza? How would they look Ivan in the eye and explain the death of that child? By reciting well-trod pieties about sin and salvation and a loving but wrathful God?

I struggle with these kinds of questions, even today, even after deconstructing and reconstructing, even after a degree in theology and a thesis focused on the question of suffering and death. Every day, despite it all, I am left with a lingering question: why must so many suffer? Where is God? Why does God allow it all?

I don’t really have any good answers to these questions, and this series of essays will not be an attempt to try to do so. Christians have been trying to do so for 2000 years, and while we have some interesting attempts, we don’t have a lot of good, satisfying answers- at least, not ones that are intellectually serious. I do think there is something to be said for sitting with these questions, for fully thrashing around in the consequences of sin and death in the world, and for trying to understand why. Maybe we’ll do so and you’ll come out the other side with no confidence in God. I think that’s highly likely for many, and no amount of Scriptural jujitsu from the Childers and Barnetts and Macarthurs of the world will do that. A mother whose child died today in a missile strike in Gaza will not be comforted to know that God wants her to proclaim Jesus Christ her Lord and Savior. Recognizing that those who cry out with Jesus, “My god, why have you forsaken me?”, do not give one shit about your idea that they are rebels against God is one small step towards deconstructing your anti-deconstruction instincts.

My father-in-law died last summer, after a three year battle with cancer. One afternoon during the last week of his life, as we made the hour drive to Cushing to spend a little more time with him, my wife asked me “why is this happening to him? Why does he deserve this?” We had a little bit of conversation, around the randomness of the universe and the lack of any sense of just deserts, especially in cases like terminal cancer. But I was unsettled, as I sat there in the passenger seat and thought about all the theology I had read and studied, all the Scripture I had meditated on. I thought about my thesis, how I wanted to grapple with the problem of suffering and what it means for God. I thought about my turn towards process theology and the concept of a limited God. I thought about Jurgen Moltmann and the Crucified God, who suffered and dies with us, in solidarity. I thought about God’s pure radiance of love for all of creation. I thought about theories of atonement, and the introduction of sin into the world, and psalms of lament, and Job’s conviction of God.

And I thought to myself, no one gives a damn right now. None of that means very much to someone watching their dad – a Christian man, a good father, a kind, compassionate and loving human being – succumb to cancer before he turned 65. All that reading and studying and glorified academic excuse-making was rather meaningless on that two-lane highway in rural Oklahoma in early August.

Nevertheless, just as I did over a decade ago, when I pushed away my faith and yet couldn’t shake that nagging feeling that God was still out there, somewhere, doing something, so did I feel in that car, and so do I feel today reading the news out of Gaza. God is still just…there. And so is death and suffering. And the Bible tells me God is love, and God is merciful, and God is just. And just how the hell am I supposed to reconcile all these things that I know to be true?

Jurgen Moltmann was drafted into the Nazi army at 16 years old, and was held by the British as a POW for three years after the war ended, during which time he absorbed the news that his country, the one he had fought for, had gassed 6 millions Jews. He became a Christian in that POW camp. After his release, he returned home and he went to Gottingen and studied theology. And all the while, he struggled to understand: what God is it that stands aside as human beings do such things to each other?

I first read his book The Crucified God in 2015, just as I was in the midst of deconstruction, but much closer to reconstruction than I knew. Moltmann is contending in this book with the problem of suffering, and does so through the lens of the Cross. Few works of Protestant theology in the 20th century were as pivotal as The Crucified God, and it certainly had a large impact on me. I’ve here numerous times about the impact of this book on my thought, and it influenced my academic work in seminary deeply. I’ve also run up against what I see as the limits of Moltmann’s thought, especially in the past couple of years as I’ve embraced the work of theologians like Stanley Hauerwas, John Howard Yoder, and Karl Barth.

The book centers around a chapter that shares a name with the book, and which takes up over 100 pages in the edition of the book I have. This chapter is the crux of Moltmann’s argument: that Christ’s Cross is the paradigmatic revelation of who God is, and what God is like: namely, that God is One who suffers and dies with humanity, in solidarity with our own suffering and dying at the hands of sin. This was a monumental idea when Moltmann published it in 1974. Moltmann had completely deconstructed and discarded the idea of an impassible God, a God who cannot and will not be changed or affected by Creation. The Unmoved Mover had been the primary theistic concept of God since Aristotle at least, and here was a German academic asserting a whole new concept in a way that could not be dismissed or written off. Here was a man who had grappled with the reality of Auschwitz as he thought about God, and had refused to be turned aside by the rote answers of traditional Christianity or postmodern atheism. This work could not, and will not, be dismissed. We must take the idea of a Crucified God seriously.

I said before, and I mean it still: this series of essays will not be drawing answers from Moltmann to try to solve theodicy. I originally conceived of this series as a full breakdown of all of chapter 6 of this book, but as I worked through it, I found myself returning to those difficult questions: how does any of this matter to the hurting and the suffering? What does a suffering God have to offer to a suffering world? I don’t know. I don’t have answers. I tried to press through and find some comforting ideas to fill these essays with. But I couldn’t and so I won’t.

These days, I affirm the Creeds of the Church, and stand well within 2000 years of theological tradition on questions such as the Resurrection, the Incarnation, and the Trinity. But I still struggle every day with doubts so vast and so deep, they should crumble this edifice of faith right off its foundations. I guess that they haven’t done so is part of the Mystery that we talk about every week when we share the bread and the wine. I want to lean into both sides of that feeling in this series. I’ll only be tackling about half of the chapter, avoiding the answers (if they could even be called that) of the back half and focusing instead on Moltmann’s critique of traditional forms of theism and his affirmation of what he calls “protest atheism”: the well-founded and just cry of anguish from those who know that the suffering of the world is undeserved and that God must be put on the stand to answer for Creation. My goal here is simple: to affirm those who question and doubt and deconstruct, not because I think God doesn’t exist, but precisely because I know God does, and because of that, I think those who suffer and questions deserve to be taken a little more seriously than many mainstream Christians want to take them.

Today marks the beginning of Holy Week, the days leading up to Jesus’ betrayal, death and Resurrection on Easter Sunday. We’ve just been through Lent, a time of fasting and meditation on the theme of mortality. Every year during this time I turn back to The Crucified God. This is why I wanted to spend this week writing through this book that has been so important to me. During this week, we journey with Jesus, through the Last Supper on Thursday night, through the Stations of the Cross into Friday morning, before Jesus breathes his last midday on Friday. We then must dwell in the grief of defeat, through the darkness of Saturday, before the sun breaks the horizon anew on Easter morning. As we remember the suffering death of Christ, there is no better time to contemplate just what this all means, not just academically, but for our world. Why does Easter matter? Or, even more importantly, why does Good Friday matter? What is in it for those who hunger and thirst and suffer and die? Those are the questions I hope we can contemplate this week.

Lovely essay, and I think you make well the point that whatever our answers or thoughts on these eternal & devastating questions, the sneering culture-war response that only our postmodern narcissism or entitlement or whatever causes our hearts & faith to be troubled by them is fundamentally not a serious one, no matter how many verses its wielders throw in.

You may be familiar with David Bentley Hart’s short book The Doors of the Sea which similarly uses Ivan Karamazov’s rebellion as a touchstone in discussing a deadly tsunami in the early 2000s, an event that like Gaza defies our capacity to see God’s hand amidst the carnage. It’s unusually short and concise by his standards and I found a very moving and serious attempt to grapple with some similar questions.

LikeLike

Thanks for reading, and for the recommendation! I’m very familiar with DBH but I haven’t read that work of us; I’ll check it out.

LikeLike

Excellent. Thank you.

LikeLiked by 1 person