The section of chapter 6 of Jurgen Moltmann’s The Crucified God, titled “The Theology of the Cross and Atheism”, has probably influenced my thinking on theological matters more than any other piece of writing. My take on theology is invariably grounded in the idea of a God who can – who did! – suffer and die. The critiques of the traditional theistic concept of God contained in this section are massively influential on how think about who God is and who God isn’t. So, as I’ve been developing this series of essays, they have all be inevitably pointing towards this particular one. The work has been figuring out how the rest of the first half of the chapter gets us to this point, and what these words are set up to do.

Tomorrow’s essay, the closing one of this series, will actually take us backwards in the text. As I’ve stated a couple of times before, what I explicitly did not want to do over the course of these essays was try to come to some form of answer to the question of why God allows suffering in the world. I find myself too often drawn to declarative statements of theology, to the detriment of doing theology as a questioning and perhaps even apophatic task. I hope I’ve corrected that tendency this week (even if yesterday’s essay shaded a little too far into firm answers.) Tomorrow, while hopefully we’ll point towards some understanding of the problem of theodicy, we won’t be seeking firm answers. We’ll be moving backwards in the chapter merely to reflect on what a Crucified God means for us.

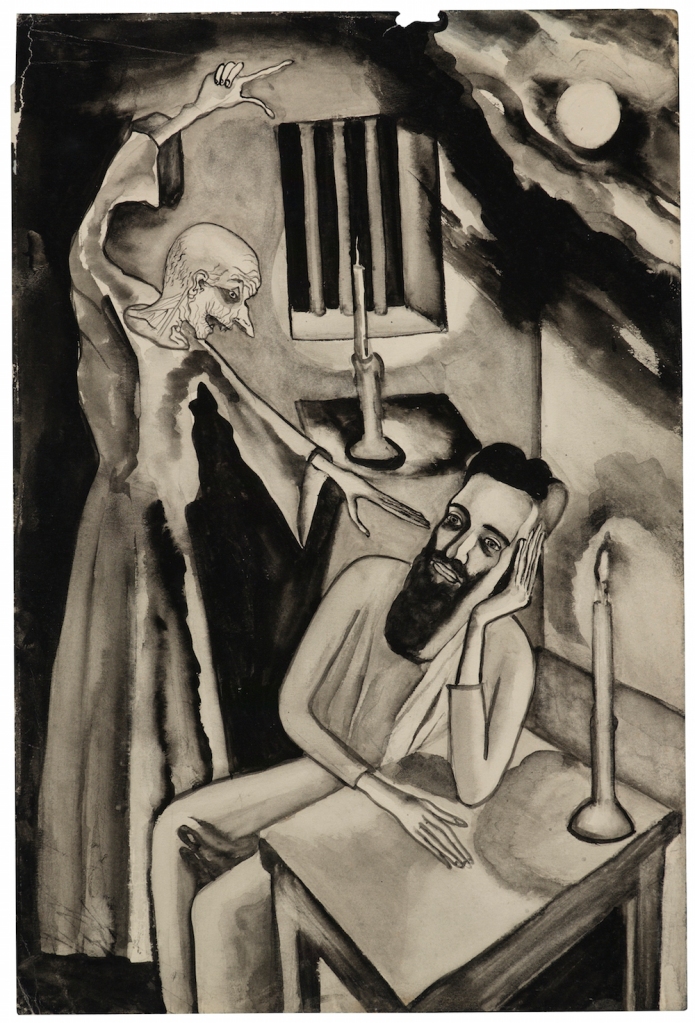

This section of the chapter lends itself very well to merely asking questions, especially accusatory ones. After leading us through the extended critique of theistic notions of God, Moltmann is ready to turn to what he calls protest atheism. Protest atheism is defined in this chapter by anguish and righteous indignation present in the Dostoevsky quote from The Brothers Karamazov that we started this essay series with:

And what sort of harmony is it, if there is a hell? I want to forgive. I want to embrace. I don’t want any more suffering. And if the sufferings of children go up to make up the sum of sufferings which is necessary for the purchase of truth, then I say beforehand that the entire truth is not worth such a price. I do not want a mother to embrace the torturer who had her child torn to pieces by dogs. She has no right to forgive him. And if that is so, if she has no right to forgive him, what becomes of harmony? I don’t want harmony. I don’t want it out of the love I bear to mankind. I want to remain with my suffering unavenged. Besides, too high a price has been placed on harmony. We cannot afford to pay so much for admission. And indeed, if I am an honest man, I’m bound to hand it back as soon as possible. This I am doing. It is not God that I do not accept, Alyosha. I merely more respectfully return him the ticket. I accept God, understand that, but I cannot accept the world he has made.

Ivan Karamazov, in The Brothers Karamazov by Fyodor Dostoevsky

The theistic form of God breaks down in the face of questions like this. The Unmoved Mover can provide no better answer to Ivan than “Because I made it to be so.” Some, in the face of the glory of the Divine, may accept this as an adequate answer, that one we must simply lay down in front of because of our very smallness. But, I think all humans, deep in the depths of their souls, know this to be inadequate. We demand more of God, because we sense God to be something more. We see the hurts and the suffering, and we too feel compelled to return our tickets.

Protest atheism that arises from such feelings is not classical atheism, which is simply the rejection of the existence of God. Moltmann says that, for protest atheism, “the question of the existence of God is, in itself, a minor issue in the face of the question of his righteousness in the world.” When we demand to know why God allows such things to happen, we are not questioning the existence of God; the question itself presumes the existence itself! Instead, we are asking: how can such a God be worthy of worship and allegiance? How can we stand the fact that God allows such suffering to persist, if God is all-powerful?

The answers classic theism posits concerning the glory of God and our inadequacy in questioning the Divine again throws up more problems than solutions. Here is Moltmann again (apologies in advance, because I’ll be doing a lot of quoting in this essay):

“And this question of suffering and revolt is not answered by any cosmological argument for the existence of God or any theism, but is rather provoked by both of these…for there is something that the atheist fears over and above all torments. That is the indifference of God and his final retreat from the world of men.” Protest atheists are not arguing against the existence of God; we all want a loving, benevolent and good God to exist. But they, and we, look around at the state of the world – we look at the little child in Ivan’s story – and we only see indifference and absence reflected back at us. No wonder nihilism has absorbed modernity! How could it not in the wake of Aushwitz and Hiroshima, of My Lai and Abu Ghraib, of Ukraine and Myanmar and Gaza and the Uyghurs? A God who is simply unmoved and unchanged is wholly inadequate to the world that that God is said to have created. To not be moved by the world is to not be dead. Wanting a loving God is fine; but how can a loving God who controls all simply sit by and allow things to exist as they do?

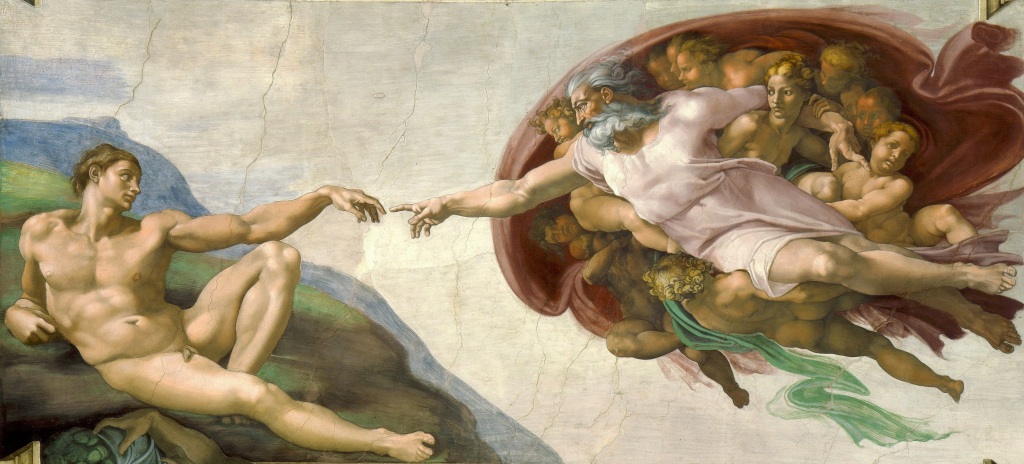

I want to take a stab one more time at the core of what is wrong with this traditional theistic God worshiped in so many churches today. Because I’ve been slightly unfair, to simply paint this God as the Unmoved Mover. I don’t think any church actually worships Aristotle’s Divine Being. I think the God worshiped in most churches today is actually a profoundly confused being. It has echoes of the Unmoved Mover: it is impassable and immovable and unchanging. But, it also declared to be wrathful and jealous (and thus not impassable), as a simple reading of the Hebrew Scriptures would reveal, but it is a wrath and jealousy that seems to center on the individual choices people make in their daily interpersonal conduct. Yet, this God is also called merciful and overflowing with love, although the nature of that love is seemingly conditional. It is a God that is said to care about all, but it also conceived of as caring about this particular congregation or group or nation or tribe a little bit more than the others. It is a God that wants success for us, and yet takes it away at the slightest whim. This God is a Frankenstein’s monster, concocted of everything we have decided this God needs to be, held together at the seams with a patchwork of Bible verses singled out and glued into place to keep everything from totally collapsing into contingency. This God is not a mystery, but an impossibility and a mirror of our own insecurities and shortcomings.

The thing that this God is not is relatable in any way. I don’t mean that God should be our best friend and close companion. I mean, a God that is merciful and compassionate, loving and just, gracious and righteous, is a God who can hear the cry of Ivan with us, and know what that depth of anguish feels like. This is a God who not only gets angry at suffering, but who knows what it means to suffer, because that distinction is crucial to any understanding of suffering that actually matters. It is a God who can relate to us in our current state, because like us, it doesn’t merely sympathize with the hurting in a merely intellectual and detached sense; like us, it feels it deep in our very Being. We recall moments in our own experience that are analogous; we re-experience that suffering in some way, and in that depth of feeling, we find solidarity with the hurting. From there, our desire to do something arises. No one who truly empathizes with hurt in this way can be unaffected, or completely unwilling to do something. The only God who matters is one who can do the same thing. An impassable, distant, and unmoved God simply doesn’t matter. God might as well be dead.

This understanding that a God who cares about our hurt must be a God who can truly understand it leads to the most important passage in all of The Crucified God. It is important enough that I am going to quote it at length, because it is the most powerful critique of the traditional ideas of God I’ve ever read:

“What kind of a poor being is a God who cannot suffer and cannot even die? He is certainly superior to mortal man so long as this man allows suffering and death to come together as a doom over his head. But he is inferior to man if man grasps this suffering and death as his own possibilities and chooses them himself. Where a mean accepts and choose his own death, he raises himself to a freedom which no animal and no god can have. This was already said by Greek tragedy. For to accept death and to choose it for oneself is a human possibility and only a human possibility. ‘The experience of death is the extra and the advantage that he has over all divine wisdom.’ The peak of metaphysical rebellion against the God who cannot die to therefore freely chosen death, which is called suicide. It is the extreme possibility of protest atheism, because it is only this which makes man his own god, so that the gods become dispensable. But even apart from this extreme position, which Dostoevsky worked through again and again in The Demons, a God who cannot suffer is poorer than any man. For a God who is incapable of suffering is a being who cannot be involved. Suffering and injustice do not affect him. And because he is so completely insensitive, he cannot be affected or shaken by anything. He cannot weep, for he has no tears. But the one who cannot suffering cannot love either So he is also a loveless being. Aristotle’s God cannot love; he can only be loved by all non-divine beings by virtue of his perfection and beauty, and in this way draw them to him. The ‘unmoved Mover’ is a ‘loveless Beloved’. If he is the ground of the love (eros) of all things for him (causa prima), and at the same time his own cause (causa sui), he is the beloved who is in love with himself; a Narcissus in a metaphysical degree: Deus incurvatus in se. But a man can suffer because he can love, even as a Narcissus, and he always suffers only to the degree that he loves. If he kills all love in himself, he no longer suffers. He becomes apathetic. But in that case is he a God? Is he not rather a stone?

Finally, a God who is only omnipotent is in himself an incomplete being, for he cannot experience helplessness and powerlessness. Omnipotence can indeed be longed for and worshipped by helpless men, but omnipotence is never loved; it is only feared. What sort of being, then, would be a God who is only ‘almighty’? He would rather be a being without experience, a being without destiny and a being who is loved by no one. A man who experiences helplessness, a man who suffers because he loves, a man who can die, is therefore a richer being than an omnipotent God who cannot suffer, cannot love and cannot die. Therefore for a man who is aware of the riches of his own nature in his love, his suffering, his protest and his freedom, such a God ia not a necessary and supreme being, but a highly indispensable and superfluous being.”

While there is so much theological richness throughout this passage, that last line is key point of everything we’ve done in these last two essays. We don’t live in the pre-modern age anymore. Our God must be able to answer the things we know to be true about the universe. Human beings, through our God-given faculties of logic and science and intelligence, have deduced much about the nature of the universe, enough that mere wonder at it all is no longer the primary human experience of nature. Wonder still exists, certainly. But we know why and how things happen, and so the role of God as simply the initiator of the unknown and majestic is behind us now. We need a God who not only made things, but who can answer for them, in a way that is better than, “Because I said so.” Let us not skip over the majesty declared by God in his answer to Job, and let us not fail to acknowledge our limited understanding of things, even in a scientific world. But let us not also be condescended to by an arrogant and inhumane God. The Scriptures grant humanity more dignity than that. God cannot simply handwave away our concerns with a light and magic show. Protest atheism is just that – a protest. God must answer.

This is the problem of the theistic God. That God is arrogant in the face of our suffering. And we cannot accept that, when we know our God is loving and humble and merciful and gracious. So how do we square this circle? Can we countenance a God who can suffer and die, as Moltmann puts it? That is the question we will close with tomorrow: not with a neatly packaged answer, but merely with an attempt to try to see what God is like, as a starting point for our grappling with the suffering of the world.