Growing up, my family attended a Lutheran church, of the Missouri Synod branch. I went through confirmation in this church, and got my first memorable church experiences there. My love for Scripture and theology was first kindled there, I think, even as in later years I rejected the faith and church. One thing I remember hearing – I don’t know from who, perhaps our pastor, or a youth leader – was that one of the ways we were different from the dreaded Roman Catholics was that our crosses at the front of the sanctuary didn’t include a replica of Jesus’ broken, bleeding body. The Catholic practice of this was morbid, and frankly not really very appropriate for a church. Our unadorned cross was much more acceptable, and was the proper way to represent the faith. Crucifixes were idols, in a sense.

I always found this to be odd, and yet also right in some way. I mean, we talked about the crucifixion a lot, and a lot of illustrated Bibles had some image of Jesus on the cross, so it couldn’t be that weird to have a crucifix in the church. But it did seem a little morbid, to have a replica of a dead body, even if it was the body of our Lord about to be resurrected. I filed the thought away, but it stuck with me enough that I still get a little niggle in my head anytime I see a crucifix. Is death really how we want to present our faith, the little voice whispers? It’s not exactly the best marketing strategy.

“The death of Jesus on the cross is the centre of all Christian theology”, writes Jurgen Moltmann in chapter 6 of The Crucified God. Evangelicals want to run past it to the glory of Easter morning. Progressives want to roll the clock back and center the life of Jesus. Both are understandable. But life, while vitally important, was always leading to this moment. And Easter morning doesn’t come without noon on Friday. Christianity is neither a mere set of ethical rules for life, or a gospel of prosperity and joy. Christianity is Christ crucified. The ethics are fulfilled in the willing and suffering death of the Servant. The glory is made manifest in the weakness and the godforsakenness. As Karl Barth reminds us, all of history points to the cross.

We’ve spent this week thinking about the reality of human suffering, and what that reality means for our understanding of who God is and what God is like. We cannot begin to answer those questions without the cross. I’ve told you multiple times this week that I won’t be giving you any firm answers or resolution to the problem of theodicy. I’m sticking to that promise. But, in Christian theology, everything points to the cross, as the measure of reality and the fulfillment of history. We can’t really answer the question of why suffering exists. But we can look at the cross to help us see what it means for God.

Moltmann also writes, quoting the Catholic theologian Karl Rahner, “The death of Jesus is a statement of God about himself.” Read that sentence again, and make sure you get all the words in the right order. The grammar is crucial. It’s easy to skim over such a sentence, reading it as “the death of Jesus is a statement about God himself,” as if we are using the death of Jesus on the cross to explain the nature of God. While we do that later on, the starting point of our work is to recognize what is really being said here: before we can make inferences about God from our meditation on the Crucifixion, we must recognize that God is making a statement first about God’s own self in the death of Jesus on the cross. Before we can speak, God must speak first, and our response must take this speaking into account. The cross isn’t just something that happened to God; the cross is God speaking to us, revealing God’s own self.

Remember what the protest atheist taught us yesterday? A god who cannot suffer and cannot even die is a very poor being. It’s a powerful condemnation of classical theism, the concept of an all-knowing, all-powerful, immutable God. But what God tells us on the cross is that God is not immutable or immovable. God on the cross is telling us, to quote Paul, that God in the form of Christ “emptied himself…humbled himself by becoming obedient to the point of death, even death on a cross.” In that moment – and always – God was and is willing to empty God’s self of power and glory, and to suffer and to die, to experience how it feels to be abandoned and to not know what the next moment will bring. This is what God tells us through the cross. God is far from an unmoved mover, and loveless beloved. God doesn’t cherish omniscience and omnipotence above all else. No, far from it.

More from Moltmann:

“When the crucified Jesus is called the ‘image of the invisible God’, the meaning is that this is God, and God is like this. God is not greater than he is in this humiliation. God is not more glorious than he is in this self-surrender. God is not more powerful than he is in this helplessness. God is not more divine than he is in this humanity.”

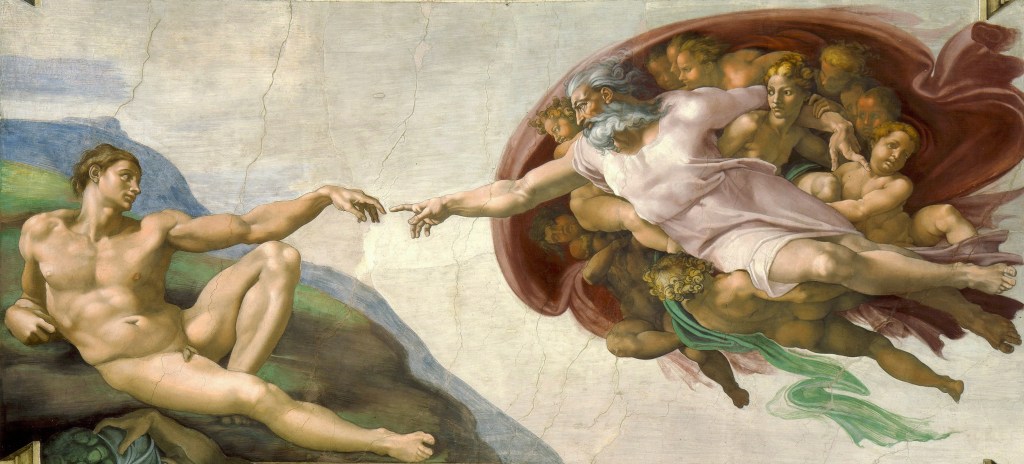

In the face of the theist and the atheist, we must point to that morbid and foolish and shocking crucifix, and insist, this is what God is like. You all are worshiping and arguing with a god that is no god at all, but is instead a dim facsimile of humanity itself. The God of Abraham and Isaac and Jacob is the still, small voice of Elijah. Blessed are the meek, said Jesus, for they shall inherit God’s earth.

This week, we have contemplated the krisis of the church, and the anguish of Ivan Karamazov. Why do we suffer, we ask again and again? It’s the question I bump up against all the time. Why is Gaza happening? Where was God in Auschwitz? What kind of justice is a justice that just allows these things to happen, only ever reacting, never proactive?

The church isn’t completely empty of answers about this. We are the hands and feet of Christ, we are reminded. We see injustice in the world, and we are called to respond. But that doesn’t get at the root of the problem. Why is it on us to solve God’s mess? God set this all in motion. Why are we on the hook? To go back to our protest atheism, why should we put up with this? Why stick around? Can we not turn in our ticket and say no, thank you?

I have some thoughts about the why questions. One day I’ll write more about those things here. I want to explore very soon the story we tell about God and the theological concept of justification, as laid out by Paul. Both of those series will touch on the whys. And I also want to spend some time grappling with process theology, a strand of thinking that I have a love-hate relationship with. There, too, we will approach the whys. But for now, because it is Good Friday, and the darkness overcomes us at the noon hour, as we prepare to hold vigil before the tomb, I don’t think this is really the time to be looking for that kind of hope. We must sit in the darkness and anguish of Friday before we can get to Easter morning.

I named this series after a line from that Dostoevsky quote we started the series with. “She has no right to forgive him,” Ivan declares of the mother who lost her child. This violence, and her suffering, deserve anguish and anger and hate. We cannot forgive such acts. We very rarely do.

We should say those words to Jesus on the cross too. You have no right to forgive your murderers. We have a share in this moment on this cross, and what an utter betrayal it is to be deprived of you, O Lord, and yet you still extend forgiveness. What right do you have?

We don’t comprehend the shocking nature of this act of forgiveness, I think. We are two thousand years on from it, and it is such a common part of the story, it has lost its ability to scandalize our sense of justice. Jesus has just been subjected to the most cruel torture and mockery, and is now being killed in the one of the most humiliating and painful ways humanity has come up with. Who in their right mind forgives in that moment? Could you?

We have no right to forgive these things we’ve had done to us. We have no right to be forgiven.. But we do have an obligation. Forgiveness is a non-negotiable. Those aren’t comforting words to whisper to the grieving mother. Ivan is right to nurture her anger and her hurt. But as a people, we Christians are called to find forgiveness, especially in the hardest moments. Not forgetfulness. Not without repentance. Not with a requirement of immediate and full reconciliation. But we do have to figure out this forgiving thing, together.

Only through the cruciform suffering love that forgiveness is motivated by do we undo the violence that leads to the cross. Jesus showed us that we defuse that kind of hate by loving, radically and wastefully and abundantly, by practicing grace. This is where we gain a glimpse of what God is all about.

Where I want to end is with Martin Luther. Moltmann, at the beginning of his section on theism (which we covered in part three), spends some time engaging Luther as a refutation of pure natural theology. Natural theology is the idea that God can be known solely from human experience or perception of the world. This is in contrast to revelation, which is the knowledge of God obtained through something like Scripture, or the actual words of God. Moltmann is not Barth, and doesn’t throughout his works wholly reject natural theology, but he does here show that he places a particular importance on the cross as divine revelation of God’s nature.

Moltmann writes that Luther used the cross as “a new principle of theological epistemology”, which is a theological way of say that the cross, rather than just being a vehicle for contemplating vicarious suffering as a spiritual practice, is instead the ground for all knowledge of God. The cross, in this sense, becomes what we have been describing above: the center and the source of all God-talk. We cannot understand the Hebrew Scriptures, the like of Christ, Easter and Pentecost, the Epistles, all of human history, without understanding the cross as the crux of it all.

For Moltmann, this reading of Luther is key to overcoming the classical theism that infects the church. Let me quote and unpack a particularly dense section of Moltmann to illustrate this further:

“For Luther understands the cross of Christ in a quite unmystical way as God’s protest against the misuse of his name for the purpose of a religious consummation of human wisdom, human works and the Christian imperialism of medieval ecclesiastical society.”

What he is saying here is that Luther viewed the cross as, like we said above, a statement of God about God, which works to undo the ways humanity appropriates the name of God to justify ungodly things like imperialism, violence, nationalism, and other Power and Principalities. A theistic God, steeped in glory and power, becomes a justification for all manner of sin. But the cross as the standard of the divine posits a wholly different God, one who becomes powerful in weakness, to quote Paul. This is the only true God, the one on the cross. “Christ the crucified alone is ‘man’s true theology and knowledge of God.’”

This is the key insight of Moltmann’s The Crucified God. God is first and foremost, primarily, found on the cross, on Friday, in Golgotha. If we truly want to know what God is like, we must not remove Christ from our crucifixes but truly contemplate him there, in his humiliation and vulnerability and death. All other knowledge of God – everything written in Scripture, Old and New, all the words of theology and devotion and praise and hymnody and evangelism – it all must conform to Christ crucified, or it is no word about God at all.

This is not an easy word. Cruciform Christianity is a hard word. As Moltmann writes, “To know God means to endure God. To know God in the cross of Christ is a crucifying form of knowledge, because it shatters everything to which a man can hold and on which he can build, both his works and his knowledge of reality, and precisely in so doing sets him free.” This gets at our on-going question about the presence of suffering. I still don’t have any answers for you. I’m not even willing to disavow the righteous protest of Ivan and protest atheism; I’m inclined to affirm it, to rage against God. But the cross is a convicting moment for all of us. We don’t know why suffering exists. But what we do know is that God emptied God’s own self of all power and glory and might, and took the form of a human being, and died a cruel and humiliating death, in the desire to ensure for us an eternal life in Christ. We cannot dismiss that action, anymore than we can dismiss the suffering of the world. It is all there in the cross, and as Moltmann says, it is something we must endure.

I said at the beginning of this series that none of this may be satisfying. It may not be. That’s ok. Its Friday. Christ’s body is on the cross, and he is dead. Today, we weep, and our hope flees our souls. Sunday morning is a long way away.

Job replied:

“I’m not letting up—I’m standing my ground.

Job 23:1-7, The Message translation

My complaint is legitimate.

God has no right to treat me like this—

it isn’t fair!

If I knew where on earth to find him,

I’d go straight to him.

I’d lay my case before him face-to-face,

give him all my arguments firsthand.

I’d find out exactly what he’s thinking,

discover what’s going on in his head.

Do you think he’d dismiss me or bully me?

No, he’d take me seriously.