The season of Lent is one of the most meaningful times of the year for me. I am a lover of the overall rhythms of the church’s liturgical calendar, and I am especially fond of the movement beginning with Ash Wednesday, through the 40 days of Lent, into Holy Week, and finally culminating with Easter. Its a theologically rich time of year, especially for a theologian like myself whose academic work focuses on suffering, both human and Divine.

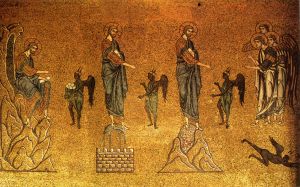

Lent commemorates Christ’s 40 days in the desert, where he fasted and withstood the Temptations he had to endure at the hands of Satan. Just as Christ sacrificed and meditated on the failings inherent in humanity, so we are called to a practice of sacrifice and contemplation. This time prepares us to walk with Christ through Holy Week, into his Suffering Death and, ultimately, the Resurrection. Scripture tells us many times Christ foreknew his coming fate, and he must have contemplated it during his days in the wilderness. Being human, he surely felt pangs of great sorrow and foreboding, alongside the assurance he felt in the righteousness of his sending.

The Temptations themselves – temptations to wield economic, religious, and political power – serve as reminders of those things which Christians are called to reject. Just as Christ refused the temptations and instead launched a public ministry predicted on humility, compassion and peace, so we are called to remember our Discipleship by refusing to live as usual, as society expects, during this time. And unlike the weak Lenten “fasting” practiced by much of popular Christianity, this isn’t a call to simply shed the trappings of the world for 40 days, followed by a post-Easter return to life as it was. No, Lent is to be a time set aside for reflection and contemplation on the kind of life we are called to at all times by Christ, the kind of life demanded by the self-sacrificial love of Christ envisioned at the end of these days by Christ’s suffering and death. These forty days are our time to remember our calling as disciples, and to re-dedicate ourselves to that way of being.

Fasting does have its place, however. For Western Christians, we can look to our Eastern brothers and sisters, who engage in a much more committed practice, where not only are diets restricted, but intense study of Scripture and the Church Fathers is accompanied by intensified prayers and spiritual exercises, as well as more time spent in and with the Church. All of this serves to preoccupy the disciple, reminding them of the overwhelming call on their lives made by Christ. We in the West, especially here in America, would be well served to pattern our own observance on these more ancient and more meaningful practices. I certainly hope to do so this year, and in future Lents.

As I mentioned earlier, Lent is a time that I feel especially called to, as a theologian who has spent much time thinking about the nature of human suffering, and the shocking reality of God’s own suffering. Christ suffered from the pangs of hunger for forty long days, not to mention the pangs of temptation he felt. We end this time in the liturgical year by observing and mourning the suffering death Christ endured, as we try to make sense of it for our own lives and our world, before we get to the beauty of Easter morning. The suffering God endured as Christ is central to our understanding of who God is. Our God is a God who suffers alongside us, who can relate to our limited existence because They have experienced it. The suffering of God on the Cross through Christ the man opens up new paths of relationality for us to have with the Divine. Lent is the time when, through voluntary self-abnegation, we ruminate on our limits, and the amazing fact that God emptied God’s self to take on those same limitations, and ultimately, even death.

Lent is my favorite time of year to revisit one of the most important books in my life of faith, The Crucified God by Jurgen Moltmann. In particular, I am drawn to my favorite passage of the book over and over again (which I will quote in full; emphasis all mine):

What kind of a poor being is a God who cannot suffer and cannot even die? He is certainly superior to mortal man so long as this man allows suffering and death to come together as doom over his head. But he is inferior to man if man grasps this suffering and death as his own possibilities and chooses them himself. Where a man accepts and chooses his own death, he raises himself to a freedom which no animal and no god can have.

…a God who cannot suffer is poorer than any man. For a God who is incapable of suffering is a being who cannot be involved. Suffering and injustice do not affect him. And because he is so completely insensitive, he cannot be affected or shaken by anything. He cannot weep, for he has no tears. But the one who cannot suffer cannot love either. So he is also a loveless being. Aristotle’s God cannot love; he can only be loved by all non-divine beings by virtue of his perfection and beauty, and in this way draw them to him. The ‘unmoved Mover’ is a ‘loveless Beloved.’

[…]

Finally, a God who is only omnipotent is in himself an incomplete being, for he cannot experience helplessness and powerlessness. Omnipotence can indeed be longed for an worshipped by helpless men, but omnipotence is never loved, it is only feared. Wha sort of being, them, would be a God who was only ‘almighty’? He would be a being without experience, a being without destiny and a being who is loved by no one. A man who experiences helplessness, a man who suffers because he loves, a man who can die, is therefore richer than an omnipotent God who cannot suffer, cannot love and cannot die. Therefore a man who is aware of the riches of his own nature in his love, his suffering, his protest and his freedom, such a God is not a necessary and supreme being, but a highly disposable and superfluous being.

[…]

The only way past protest atheism is through a theology of the cross which understands God as the suffering God in the suffering of Christ and which cries out with the godforsaken God, ‘My God, why have you forsaken me?’ For this theology, God and suffering are no longer contradictions, as in theism and atheism, but God’s being is in suffering and the suffering is in God’s being itself, because God is love.

Today is the day we take the ashes, in remembrance of our own mortality and impending death, but also in the hope that the love of God has overcome that death. God was able to do this through taking on willingly that death, out of love, and thus to show death impotence in the face of what really matters. So, let us remember, as we enter this season of denial, suffering and sacrifice, that through it all, we are called to love one another in a new and radical way, as God loves, not because it is a duty, but because we can know what it means to love and be loved.