In the last essay in this series, we walked through two alternate and opposed readings of the Gospel of Luke, and specifically, how God’s work in the history of the world is interpreted. As we saw there, God does not call us to be agents of effective action in our work for justice and peace; rather, God calls us to be agents of love, through the works of charity. As I pointed out back at the beginning of this series, this is a seemingly controversial and radial statement to make in progressive Christian circles, where charity is viewed so often as a band-aid of sorts, slapped over the hurts of the world with some view to curing, but mostly with the intention of covering up and ignoring. While this instinctual suspicion is not wrong, considering how charity has come to be weaponized in our capitalistic world as a tool against just social change, Hauerwas is calling us to a different, deeper and more holistic understanding of what charity should be for the Christian concerned with social justice.

Today’s post builds on the last: if we accept that the work of making history come out right is God’s work, and not ours, then how can we know God’s work when we see it? As we noted last time, too often God’s name is applied to a range of works and deeds that are completely anti-Christian and against what God desires for our world. This makes things very confusing! How are we limited human beings supposed to identify God’s work in the world?

Luckily, we have an example, by looking at God’s very own self in the form of Christ, and the work Christ did for us, as laid out in the Gospels. Want to know what God’s work in history looks like? Read the Gospels. Want to know what grafting our story into Christ’s looks like, what kind of concrete action is required of us if we are going to be called “Christians?” Read the Gospels. Christ is a living, breathing example of not just God’s work in remaking all of history, but in what kind of work we are called to do alongside God.

Hauerwas begins by pointing out that is would be natural for us to assume that, because God’s task of setting the world right is so big, it naturally requires the mechanism of power, and thus, we like to think this must mean that Christians are called to seize the levers of power, or to at least ally with those who control them. As Hauerwas illustrates so well, “it is natural to assume that Christ should have gone straight to the top – if not Caesar, at least Pilate…Or at least, failing there, then Jesus should have gone to the Left – the Zealots or some other group of revolutionists who opposed Caesar and Pilate.”

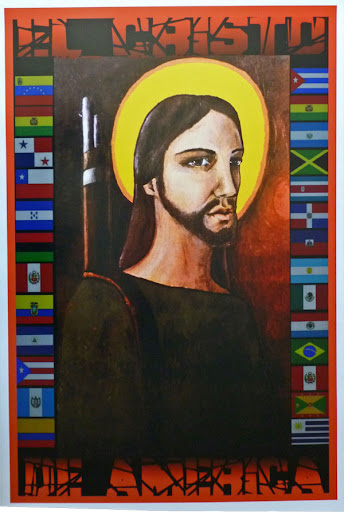

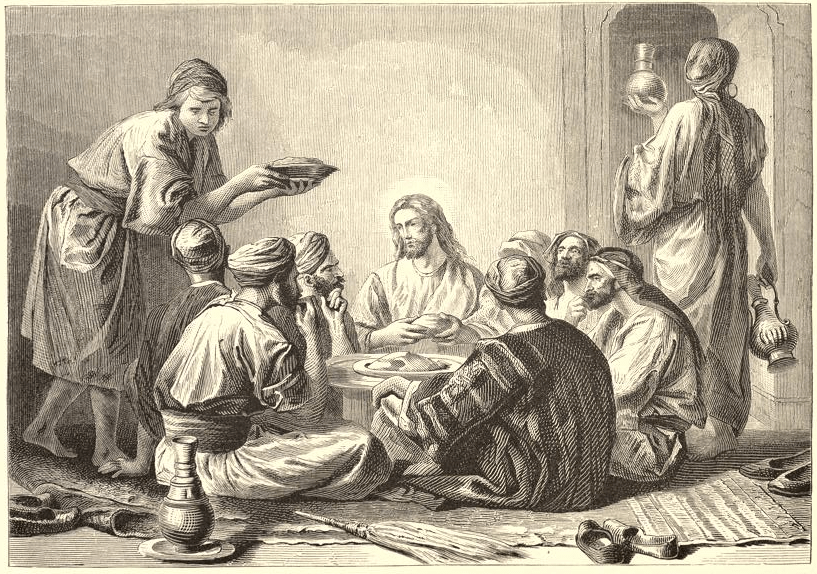

But, as we see in the Gospels, this is not the path Christ took in his work of remaking the world. “Instead,” Hauerwas writes, “we notice in Luke it is emphasized that Jesus came to the poor and the sinners.” And further, “Jesus in Luke is almost exclusively concerned with the poor.” The first and greatest clue to how Christians are called to be in the world is to see that Christ spent his entire ministry among the poor, among the oppressed, among the sick, among the foreigners, among the unclean and unwelcome.

On the other hand, it’s not like Jesus hung out with the poor, but ignored the rich and powerful. Oh no. Hauerwas points out, “it is to the poor that the good news comes, not those of strength or wealth. Indeed, it is exactly the latter who are in deep trouble as their wealth and strength gives them the illusion they can be safe in this world. Thus Christ says with no qualification, ‘none of you can be a disciple of mine without parting with all his possessions.’” Jesus’ choice to live among and for the poor is also an active commentary on the rich and powerful; the poor are chosen, while the rich are not, to host the presence of God in the world.

But why the poor? If God is remaking the history of our world, wouldn’t it make more practical sense to reshape the loci of power? I mean, hanging with the poor is great and all, but if you really want to make change happen, shouldn’t you be influencing power, rubbing elbows, making policies, focusing power? But, again, with God, it’s not about practicality, or effectiveness, or “getting results”, at least as the world would count those things. God is with the weak because in the weak, the poor, the powerless, and the meek, we most clearly get to see what God is like, and what God wants for the world. Hauerwas writes, “what we see involved in Christ’s concern for the poor and the weak is how God chooses to deal with history, namely, through the weak. But what he does for the weak is not make them as the world knows strength, but rather provides us with a savior who teaches us how to be weak without regret.”

Weakness is the key. Effectiveness is eschewed, because weakness is not effective according to the power hierarchies of the world. And thus, our work of charity in the world becomes not about what we can achieve, but about the goodness of doing a kind deed for someone else for the sake of itself. “For we cannot give charity if we think that charity is a means to renew the world – that is, if charity is justified by its effects.” To do charity without the intention of acting with love, but with the intention of using that charity for a greater end is to turn that human being you are serving into a means to an ideological end. This is the key point on which this all turns. Just as Christ was offered all of the effective means to change the world in the Temptations, if only he would willingly sacrifice a small measure of his dependence on God, so we are called to turn away from the lure of easy, assured fixes if they cause us to stray from being a part of the story of Christ.

This seems like a rather hopeless fate for Christians. If we aren’t supposed to work with the goal to make the world a better place, what’s the point of social action? Wouldn’t we just be better off being nice to others and minding our own business? Not at all. Our ineffective stance towards the world has purpose: it makes us a part of God’s story, as witnessed in Christ. “What we are offered in Christ is a story that helps us sustain the task of charity in a world where it can never be successful…We are freed in this respect exactly because we know that charity is not required in order to justify our existence, to rid us of guilt, but because it is the manner of being most like God.” We are charitable, meek, loving, weak, ineffective because that is the form God took when God came into the word and took human form. God was not concerned with effectiveness when embodied as Christ; if that would have been the case, I doubt God would have been content with dying an early and violent death! To quote Hauerwas one final time:

“For we are commanded not to be revolutionaries, or to be world-changers, but simply to be perfect.”

One of the most powerful theological concepts out there is the idea of kenosis. Kenosis is a Greek word applied to Christ, which literally means “the act of emptying.” It derives from the great hymn of Philippians 2, specifically verse 7. Here is the context:

5 Have this mind among yourselves, which is yours in Christ Jesus, 6 who, though he was in the form of God, did not count equality with God a thing to be grasped, 7 but emptied himself, by taking the form of a servant, being born in the likeness of men.

Christ emptied himself, he made himself nothing, in order to do not his own earthly, human will, but in order to let God’s will enter him and guide his actions. Paul exhorts us in this letter to do the same: “Have this mind among yourselves.”

I think an understanding of kenosis can help us start to make sense of what Hauerwas is doing in this essay. For so many of us, the drive to make the world better, to fight injustice, to do the work of changing things becomes an overwhelming urge. Not a bad one, mind you, but one which over time becomes less and less about God’s will and more about our own. Be honest. When you go out to work for social justice, are you opening your spirit to God, asking God which direction to lead, and emptying yourself so that God’s will – whatever that may be – can guide you? Is it about a humble, self-effacing, empty way of encountering the need in the world? Or have we got the answers, got all the plans? Are we looking for those social media opportunities, so we can let the world know what is happening, what we are doing?

Emptying ourselves means letting go of the need to have control over what history looks like. It means not having all the answers. It means listening for the still, small voice of God that directs all of creation towards its fulfillment. It means simply showing up, being present to those near us, and acting with a kenotic love and charity towards those we encounter, not in the hope of reshaping the world in the image of some abstract idea of justice, but instead, just because it is the best, most Christ-like thing to do right in that moment. No, it probably won’t be systematic and organized all the time. But that’s ok. Faith means we trust that God can use each little moment of genuine love and connection among us to craft a better world for all.

Now, I can still feel all my fellow progressives and social justice-minded folks squirming at best, or more likely feeling disgusted or dismissive at this point. And let me tell you, I feel you. If this is where the chapter ended, and where Hauerwas stopped speaking, I would be too. But we aren’t done! Our next essay will be one more Scriptural illustration of this dichotomy between effectiveness and charity before we dig into the meat of how being ineffective still leads us to fighting against injustice, against suffering, and against oppression. Stick with me.