All of the sudden, the words I sing every day at morning prayer echoed in my head. Send out your light and your truth, that they may guide us and lead us to your holy holy hill and to your dwelling. I felt dizzy. This was God’s holy hill: the Hill. And that apartment, with the broken tricycle out front, next to Ruth’s? That was God’s dwelling. God lived right there, in that actual apartment. God lived in Ruth’s hands.

What had I been thinking by praying those words without really paying attention?

They were real. Above me, above the projects and Ruth’s tears, above the wrecked roofs and broken doors and every mistake I’d ever made in my life, was the dark sky, luminous in the east. And in my hands were some Cheerios, some lettuce, and a loaf of bread.

I was going to keep giving that food away. What I glimpsed in the projects was the last thing I’d expected growing up: that because God was about feeding and being fed, religion could be a way not to separate people but to unite them.

It wasn’t that class and race disappeared in the blinding light of God. It wasn’t that the painful cultural splits among believers – over abortion or homosexuality or the role of laypeople – were erased by invoking the name of Jesus. It wasn’t even that people on the Hill who prayed with me or blessed me or told me about their churches necessarily shared my own peculiar ideas about God. But something happened when I brought a plastic bag full of lettuce and potatoes and left it on Ms. Robinson’s table. Something happened when Ruth fixed me a plate of neck bones and green beans and made me sit down to eat it, or Ty-Jay offered me a sip of his ice tea. The sharing of food was an actual sacrament, one that resonated beyond the church and its regulations, and into a real experience of the divine. I wanted more.

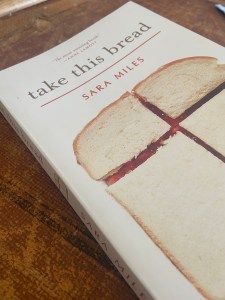

Sara Miles, Take This Bread, 196-97

Tag: Sara Miles

Excerpts #5

Conversion isn’t, after all, a moment: it’s a process, and it keeps happening, with cycles of acceptance and resistance, epiphany and doubt. As I struggled with bread and wine and belief over the following year at St. Gregory’s, it stayed hard. I began to understand why so many people chose to be “born-again” and follow strict rules that would tell them to do, once and for all. It was tempting to rely on a formula – “accepting Jesus Christ as your personal Lord and savior,” for example – that became itself a form of idolatry and kept you from experiencing God in your flesh, in the complicated flesh of others. It was tempting to proclaim yourself “saved” and go back to sleep.

The faith I was finding was jagged and more difficult. It wasn’t about abstract theological debates: Does God exist? Are sin and salvation predestined? Or even about political/ideological ones: Is capital punishment a sin? Is there a scriptural foundation for accepting homosexuality?

It was about action. Taste and see, the Bible said, and I did. I was tasting a connection between communion and food – between my burgeoning religion and my real life. My first, questioning year at church ended with a question whose urgency would propel me into work I’d never imagined: Now that you’ve taken the bread, what are you going to do?

Sara Miles, Take This Bread, pg 97