Any long time reader of mine knows I have a deep affinity for liberation theology. My earliest ventures into theology were by reading the words of James Cone and Oscar Romero and Gustavo Gutierrez. The highly political and radical nature of liberation theology strongly appealed to me, coming as I was out of my work in progressive politics and my early academic work in political science. Ideas like the “preferential option for the poor” were intoxicating to me, as much of my understanding of Christianity growing up never included such concrete and political concepts.

Stanley Hauerwas opens his essay, “The Politics of Charity”, by reflecting on liberation theology, and its approach to a world of injustice and deprivation. “Thus liberation theology,” he writes, “aims not just to aid the poor but to give the poor the means to do something structurally about their plight.” This is a succinct and accurate statement of the primary focus of the politics inspired by liberation theology. The reason liberation theology has become so popular on the religious left is exactly this emphasis on the empowerment of the poor, especially when considered in light of the politically-prominent American Christian Right’s focus on conservative, capitalist-friendly politics that alienates and disempowers those who aren’t the wielders of captial. Liberation theology has become one of the primary banners of the scores of Christians who can’t find a home in the more traditional public face of Christianity in America. Equally appealing is the permission structure it erects for doing political work under a religious banner; too many churches have long talked about the poor and the orphan, while doing little for them in a concrete, material way. Liberation theology, on the other hand, insists that actual, physical liberation is a necessary corollary to salvation, both for the oppressor and the oppressed.

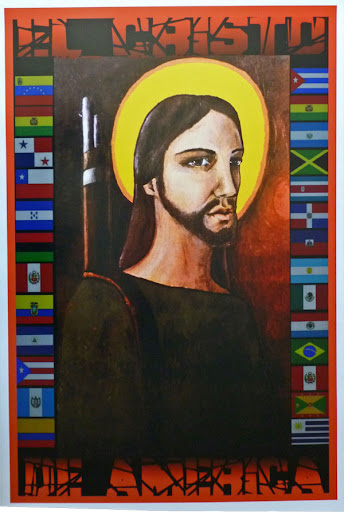

Despite this good work, liberation theology also has its own shortcomings, wrapped up in its own fealty to leftist politics and Third World class struggles. Hauerwas begins his essay highlighting this tendency. He quotes from a piece by Camillo Torres, a Colombian priest, revolutionary, and socialist, who wrote that for “love to be genuine, it must seek to be effective.” Hauerwas expands on this, writing “the logic of this position requires if revolution cannot come by peaceful means, the Christian in the name of charity must be willing to use a gun.”

The “effectiveness” of the Gospel is at the center of Hauerwas’ essay. Are Christians required, in the work we are prompted to by the love of Christ, to be effective? Should we be focusing on doing things that can ensure some sort of positive outcome, embracing a variety of means in pursuit of one salvific end? Or do we need to adhere to a different accounting of effectiveness, one more predicated on intentions and values, on actions and virtues?

Hauerwas is clear very quickly, taking the latter position. “It is just such a conclusion,” he writes in reference to his extrapolation of Torres, “that indicates that something has gone terribly wrong in the linking of charity with effectiveness.” To focus on the effectiveness of what we do is to focus on the wrong criterion of action. Instead, Hauerwas believes, “what becomes all important is how that kingdom is served…what is important is how Christ taught us to care for our neighbor.”

This here is the central point Hauerwas is making, and his large critique of much of popular Christianity – on the left and the right – in today’s world. Too often, we Christians judge the work we are doing based on the standards of what is politically or socially effective under the rules of the game as laid down by the world. But Hauerwas is reminding us here that the standard we should be basing ourselves on is not the world’s, but the standard of love as laid out by Christ – “and by the world’s standard Christ was ineffective.” When deciding what to do to face down injustice, Christians shouldn’t be asking “what can we do to wield power for good?”, but instead “what does Christ require of us?”

Now, it is crucial to understand: this isn’t a directive to withdraw from the work of the world. Too often, ungracious readings of Hauerwas accuse him of just that sort of sectarianism, of wanting to pull back from the world and be piously righteous from the outside. But this isn’t the intention of his critique of effectiveness. Instead, he writes “a politics of charity rightly formed should help the world redefine what politics involves.” The politics of charity, which is what Hauerwas posits in place of the politics of effectiveness favored by so many socially-minded Christians, should be predicated on presenting an entirely different set of priorities, values, and emphases to the world, as it reminds Christians of the crucial and irreconcilable difference between the church and the world. “For the politics of the world is perverted because it takes power and violence to be the essence of human and institutional relations.”

The job of the Church is to present a new way of doing politics, one predicated on a different understanding of what is and isn’t effective. “In a world where the value of every action is judged by its effectiveness, it becomes an effective action to do what the world understands as useless.” This is necessary for Christians because we have a different understanding of purpose and meaning for humanity than the world does. The priority of the world is under-girded by a drive for mere survival. But Hauerwas calls this desire to survive an “illusion” for disciples of the Crucified One. “The very heart of the Gospel,” he writes, is “that what we have to fear is not death, but dying for the wrong thing.” When this shift happens, priorities and values shift radically. When the situation the world is in is no longer viewed through the lenses of effectiveness and survival and scarcity, things take on a whole new color.

Before moving along with his argument, Hauerwas ends with one final critique of liberation theology. Within this branch of thought, one of the driving forces is the idea of the preferential option of the poor. This means that, for Christians, all social action becomes justified if and only if it is meant to alleviate the poor and suffering of some form of oppression. As Hauerwas writes, this focus too often becomes the ultimate good of liberation theology, and thus idolatrous. As he writes, “For when the poor become the key to history it is assumed that the aim of the Christian is to identify with those causes that will make the weak the strong.”

Of course, the plight of the poor is a crucial concern for Christians, and one we are all called to address. But, being poor does not make one a Christian automatically, and working to ease oppression or poverty is not automatically Christian work no matter what form it takes. This is related back to the first point above: when any form of revolution is given the sheen of truth, then the use of non-Christ-like means of action becomes easy to baptize. “I am sure that the poor have a special place in God’s kingdom, but I am equally sure that the Christian life involves more than being oppressed or identifying with the oppressed.” This isn’t to say that Christians should only be serving the Christian poor; we have a duty to all peoples, wherever they are, especially if they are oppressed. But it does mean that the means envisioned by some groups of the poor may be incompatible with what it means to be a Christian, and ways in which a Christian should and should not act.

The work of the Christian in the face of overwhelming oppression and poverty is not to provide freedom or power at any cost. Instead, it is to ask how we can do this work in a way that puts us in sync with the story of Christ, and then to only accept the forms that are Christian in nature, whether or not they are deemed effective by the world or not. The point, in short, is not the end result; we are not utilitarians, after all. The point is, what should Christians do in light of the life, death and resurrection of Christ? This is the driving question behind Hauerwas’ politics of charity, which we will begin to unpack in my next essay.

One late note before we move on, in defense of liberation theology. As I stated at the opening, I have long loved liberation theology. My earliest days as an aspiring theologian were steeped in liberation thought, nurtured by the words of James Cone and Oscar Romero. I am still deeply indebted to them; in fact, I have an icon of Bishop Romero hanging over my desk, as a visual reminder of what theology is all about, in the end. I still believe liberation theology is an important strain of theological thought with much to teach the church. In a world of increasing inequality, and growing political and social oppression, it is as important as it ever was for the church to speak clearly and forcefully against injustice and for those who are oppressed and hurting in the world, whoever and wherever those people may be. Liberation theology is a fully formed tradition that can provide powerful words and ideas to help the church carry out this task. There is much to be learned and taken from this tradition.

And there is perhaps no better place to look than at the words and life of Bishop Oscar Romero. Castigated in his lifetime by more extreme adherents to liberationist thought for being too conservative or too timid, Romero never lost sight of the Cross as the generating image behind liberation theology. Romero, in his fight to prevent the Church from being co-opted by conservative, reactionary forces driven by power and wealth in El Salvador, was equally unwilling to let the Church be co-opted by Marxist and radical liberation fighters among the people. Instead, the church stood as a third way between these two warring factions, both of which claimed the mantle of popular assent, but neither of which in reality held it. Romero understood that the hope of the people of El Salvador – and of oppressed people everywhere – lay not in economic growth or socialist ideology, but in the Cross of Christ and the community of faith that is Christ’s body. Romero expressed it perfectly, when he preached:

The political circumstances of peoples change, and the church cannot be a toy of varying conditions. The church must always be the horizon of God’s love, which I have tried to explain this morning. Christian love surpasses the categories of all regimes and systems. If today it is democracy and tomorrow socialism and later something else, that is not the church’s concern. It is your concern, you who are the people, you who have the right to organize with the freedom that is every people’s. Organize your social system. The church will always stay outside, autonomous, in order to be, in whatever system, the conscience and judge of the attitudes of those who manage or live in those systems or regimes.

The church is not capitalist. The church is not socialist. The church is the Church, and its work is Christ’s work, which may be of no concern to the way of the world – which may not be terribly “effective” – but which are of ultimate concern to God.