Christians have no greater task in the world than to be the church. This is a rather innocuous sounding claim that is actually rather radical when the implications are thought through completely. For what it means is that the task of Christians in the face of world events is not to analyze the best political or social action strategy, and then pursue that with technocratic efficiency. Instead, it is to see what is happening in the world, and then ask themselves, “what should I do about this in light of the death and resurrection of Christ?”

This is as true now, in the face of the coronavirus pandemic, as it ever was. So, what does the work of the church look like right now? How can we Christians be the church during a pandemic? Over at The American Conservative, Rod Dreher draws our attention to how Christians of the past were the church during a time of pandemic. He quotes at length the historian Tom Holland, who writes:

First, at the end of the second century, and then again in the middle of the third, bowls of wrath were poured out on the Roman empire. Of the second pandemic, a historian would subsequently record that “there was almost no province of Rome, no city, no house, which was not attacked and emptied by this general pestilence”.

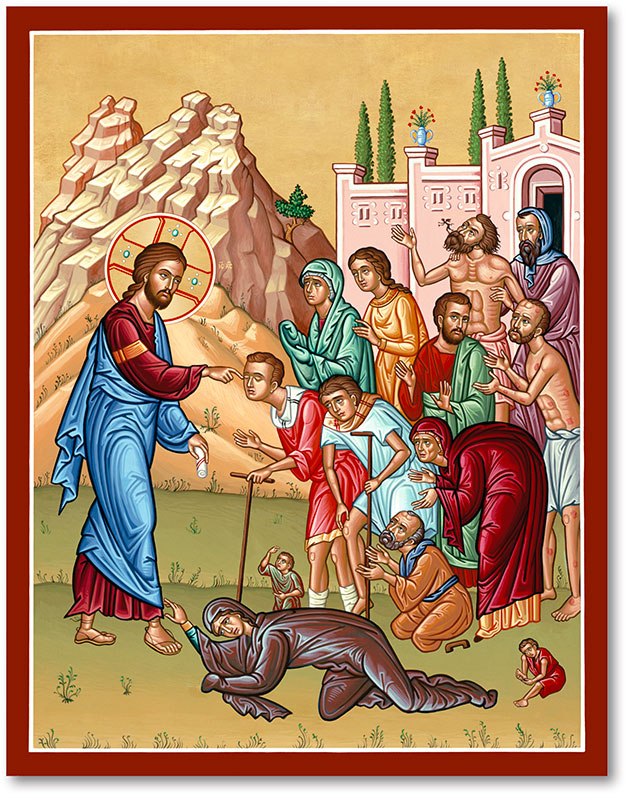

Did it mark, then, the breaking of the cities of the world foretold by St John? Many Christians believed so. Fatefully, however, it was not as worshippers of a God of wrath that they would come to be viewed by many of their fellow citizens, but as worshippers of a God of love: for it was observed by many in plague-ravaged cities how, “heedless of the danger, they took charge of the sick, attending to their every need and ministering to them in Christ”. Obedient to the commands of their Saviour, who had told them that to care for the least of their brothers and sisters was to care for him, and confident in the promise of eternal life, large numbers of them were able to stand firm against dread of the plague, and tend to those afflicted by it.

The compassion they showed to the sick – and not just to the Christian sick – was widely noted, and would have enduring consequences. Emerging from the terrible years of plague, the Church found itself steeled in its sense of mission. For the first time in history, an institution existed that believed itself called to provide compassion and medical care to every level of society.

The revolutionary implications of this, in a world where it had always been taken for granted that doctors were yet another perk of the rich, could hardly be overstated. The sick, rather than disgusting and repelling Christians, provided them with something they saw as infinitely precious: an opportunity to demonstrate their love of Christ.

Jesus himself, asked by a centurion to heal his servant of a mortal illness, had marvelled that a Roman should place such confidence in him – and duly healed the officer’s servant. By the beginning of the fourth century, not even their bitterest enemies could deny Christians success when it came to tending the sick. In Armenia, the Zoroastrian priests who marked down the Krestayne as purveyors of witchcraft were at the same time paying them a compliment. When the Armenian king became the first ruler to proclaim his realm a Christian land in 301, his conversion followed the success of a Christian holy man in curing him of insanity – and specifically of the conviction that he was a wild boar.

Then, just over a decade later, an even greater ruler was brought to Christ. Constantine embraced Christianity, not out of any concern for the unfortunate, but out of the far more traditional desire for a divine patron who would bring him victory in battle; but this did not mean, once the successful establishment of his regime had served to legitimate Christianity, that Christians among the ranks of the Roman elite turned a blind eye to their responsibility towards the sick.

Quite the opposite: “Do not despise these people in their abjection; do not think they merit no respect.” So urged Gregory, an aristocrat from Cappadocia who in 372, 60 years after Constantine’s conversion, became the bishop of a small town named Nyssa. “Reflect on who they are, and you will understand their dignity; they have taken upon them the person of our Saviour. For he, the compassionate, has given them his own person.”

This is a wonderful example of what being the church looks like in the world. Christians in the first centuries were different from the world, in that they did the kind of work (like healing all during the plague) that made the world take notice and look on in wonder. And in doing so, they exemplified the moral character of Christ, exhibiting love, mercy, kindness, compassion, and joy.

Which is really the point. Christians, as the church, are different from the world not for the sake of being different, but for the sake of living into the character of Christ. Some Christians today take pride in “not being of the world” in a showy sense, in that it is in obvious in a very deliberate and manufactured way. But, what they fail to realize is that if they aren’t acting from love, from a concern for the needy and the poor, from a place of humility and regard for the Other, then they are just loud people doing weird, not very impactful things.

That is especially true right now, during this pandemic. As I wrote about yesterday, a very loud group of people, many of whom (based on their political persuasion) would almost certainly claim the title “Christian”, think they are being the “Church” just by being contrary, for the sake of contrarianism, not for the sake of Christ. But right now, being the church doesn’t look like defying science and public health guidelines. Right now, being the church looks like it always does: a community of faith, built on love for our neighbors, concern for the weak, a desire for righteousness, and practices of mercy and compassion.

Now, does that necessarily mean we all run out and throw ourselves on the frontlines of the outbreak, a la the second century Christians Holland describes? I don’t think so. We have medical professionals in today’s world, who don’t need us getting in the way of doing the work they have trained their whole lives to do. So what does it look like?

I don’t have the answers to that question. Perhaps it looks like, if you are young and healthy, going to the grocery store for your elderly neighbors, so they can stay in and stay safe. Perhaps it means sitting on the front lawn of the lonely old man down the street and chatting with him. I know it definitely looks like doing everything we can to keep people safe and healthy, even at the expense of our own comfort or routines. Its like the old church camp song says: “And they will know we are Christians by our love.”