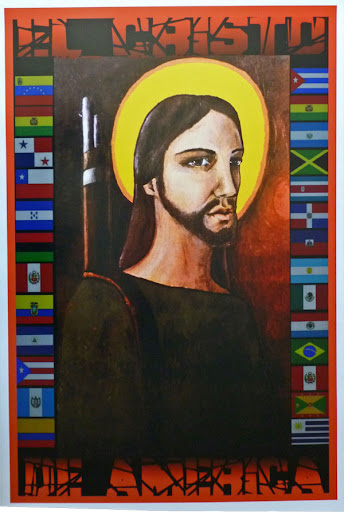

In opening his essay with a critique of liberation theology, Hauerwas was underscoring his main point: that Christian political engagement – and the theology under-girding it – is not judged on its effectiveness in the realm of worldly politics, but instead is to be judged on how Christians engage. In other words, the point for politically-conscious Christians should not be the end result, but instead should be the tactics and strategies we take to achieve things. Hauerwas describes his own purpose in writing as trying “to suggest how Christians should care for the poor, that is what form our charity should take, and in what sense such a charity is politics.” This here is the thesis statement of the entire essay. In future posts, I will get further into what Hauerwas means when he means “charity” but, following the track of the essay, first we must talk about the Gospel of Luke, because for Hauerwas, there is no good political theology if it is not grounded in the life and words of Christ as found in Scripture.

“In Luke,” Hauerwas writes, “we find the historical significance of Christianity, or as Luke prefers, the Way, most dramatically represented.” The Gospel of Luke is the most Gentile-centric of the four gospels we find in Scripture. Luke, most likely a Gentile himself, was writing his account of Christ and the early church to a Gentile audience, trying to bridge the Jewishness of Jesus to the Gentile culture of Greece and Rome. Luke was likely a disciple of Paul, himself someone famous for his commitment to bringing together Jews and Gentiles in one body. So, as he writing his account, Luke is looking to connect what could seemingly be sectarian or provincial tale of a far-flung religious disturbance to the wider happenings of the world, to make his readers understand how Christ is not merely another story on the world’s stage, but is instead the story from which the rest of history obtains its meaning. To quote Karl Barth:

For Jesus Christ is the fulfillment of the covenant concluded by God with Abraham, Isaac and Jacob; and it is the reality of this covenant -not the idea of any covenant – which is the basis, the meaning and the goal of creation, that is, of everything that is real in distinction from God.

Understanding Luke’s Gentile audience is crucial to Hauerwas’ essay because Luke was perhaps the first Christian thinker (or perhaps the second, after Paul) to communicate the world-encompassing importance of the Christ event, and by extension, to make the claim that Christ is the key component of God’s salvation of the entire world, and not just the Jewish people. God fulfills the covenant of Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob in the work of Christ on Cross, and that work extends to all people, everywhere.

This concept is called a “theology of history”; that is, it is the work of examining the arc of history and the meaning of the human story through a theological lens. In Luke, Hauerwas perceives a very specific theology of history. He writes, “the fact that dominates Luke’s Gospel and Acts is that the Gentiles have been grafted onto the promise to Abraham.” This is Luke’s theology of history, and by extension, also Paul’s: through Christ’s work on the Cross, the Way is made open to all people to accept God’s promise of building a nation of people, as innumerable as the stars, and under the everlasting promise of God’s good grace first made to Abraham and the people of Israel in their covenants.

So, what does this have to do with charity and effectiveness? Hauerwas correctly sees that this promise of God, and its subsequent transformation into a understanding of God’s work in history, takes on radically different valences in the context of a regional subpower’s relationship with a deity than it does in the context of a globes-spanning religion backed by the military and economic power of nation-states. To put it more simply, Luke’s theology of history means something radically different in America in 2020 than it did in Palestine in 70 CE.

Hauerwas explains the reason this is true by identifying the implications of Luke’s theology of history: “This view of history would seem to mean that in a fashion Christians have the key to history – that is, we know its meaning and we know where it is going.” If, as Luke claims, the history of all the peoples of the world is tied up in the salvation offered by Christ, then surely those of us who call ourselves Christians have some kind of stake in how the world turns out, right? If Christ extended the Abrahamic covenant to all of the world, then we seemingly have a covenantal duty to make sure that all the nations of the world become part of God’s nation. “For the Christ we Christians serve seems to commit us to having a stake in how history comes out.”

This creates a problem. If we Christians have a stake in the course of history, what happens when that history goes badly? If we, through the promise of the universal Christ, are responsible for the shape of world events, what does, for instance, the Holocaust mean for how well we are doing our jobs? The only logical answer, of course, is that we must fix it, and more importantly (in this understanding of history), we have a Christian responsibility to do so! And a necessary corollary of that responsibility becomes that we must change the world no matter what it takes to do so. The goal of God’s kingdom, brought about by our actions, is so important that we must get there, that we must not let the fallen nature of humanity and our misguided will be impediments to the goal. Take action, history seems to tell us, and let the future judge the results and not the actions.

Are you starting to see how this kind of thinking – this misinterpretation of Luke’s theology of history – has led to so much evil and wrong in the world, done in the name of Christ? If we are responsible for the world – if our telos, our end goal, as Christians is the salvation of this world with a remit to fix things now – then we feel empowered to pursue almost any means to achieve that ends, as long as we are sure to state clearly throughout that we are Christians. Thus, God’s name can be invoked, for instance, in justifying war, as long as that war’s stated goal is the betterment of the world in accordance with the covenantal heritage extended to us through Christ.

At this point, it becomes rather simple for actors with bad or impure intentions to invoke the imprimatur of Christ to justify a whole host of actions contrary to the life of Christ. In short, in order to combat injustice done not in Christ’s name, this model lets us commit injustices to defeat those other injustices, as long as we confidently declare God to be on our side. You can see in this kind of reasoning, for example, the route some Christians take to justify the death penalty; we must stop murder by committing murder, because somehow our own murder is more just. Further, when paired with certain takes on atonement and missiology, more harm can be done, through justifications tied to a wrathful, retributive God, and a divine mandate to convert the world to our religion or else.

It’s not just bad or disingenuous actors who use this justification, either. Our rightful shock and disgust with the path human history has taken – and our own implication in the guilt of that history – seemingly requires even those of us justice minded folks to feel we need to “fix” history in order to do the work of God’s kingdom. Hauerwas is worth quoting at length here:

Thus our history gives us an even more powerful reason to combine charity with power and the effectiveness it brings. For we think the way to learn to live with a wrong is to make it a right. Indeed our history has been flawed, but we can rectify our past by changing our history to make it come out right. In other words, our very guilt makes us require a God not just of charity but also who gives us the power to do good. We want him to be a God of love, but a love that is coupled with the power to make that love effective.

This brings us back, then, to effectiveness and charity. Luke’s theology of history is important to our study because how we read it profoundly influences how we believe Christians are meant to act in the world. In the reading we have been examining so far, Luke’s theology of history seemingly hinges on what it is we are after – that is, the focus is on what we – emphasis on the “we” here; we are the primary actors in this telling of the story – imagine a just world ruled by God’s covenant must look like in the end. From here, acting in charity – that is, acting with that which Thomas Aquinas called “the most excellent of the virtues” – is not the primary focus of Christian social engagement, but rather, effectiveness is: how much can you get done, and what is the quickest way you can do it?

But, as Hauerwas has started to open our eyes to, this is a “profound misreading of Luke.” Please forgive me, but I must quote him at length one more time in order to unpack this point more effectively (emphasis is all mine):

For what Luke suggests is not that Christians are called to determine the meaning of history, that we have a responsibility to make history come out right, but rather that that is God’s task. What God has done in Israel and Christ is the meaning of history, but that does not mean it is the Christian’s task to make subsequent events conform to God’s kingdom. Rather the Christian’s task is nothing other than to make the story that we find in Israel and Christ our story. We do not know how God intends to use such obedience, we simply have the confidence he will use it even if it does not appear effective in the world itself…For in the form of the life of Christ is the form of how God chooses to deal with the world and how he chooses for us to deal with the world.

Phew. That’s some good theology right there.

Alright, let’s unpack that a little bit. In this passage, Hauerwas is posing the first look at the alternative he is presenting to the “politics of effectiveness” that comes out of that other reading of Luke. Rather than counting how close we come to abstract vision of how we think God would want the world to look (a exercise of monumental hubris if you really think about it for a second), the proper reading of Luke’s theology of history is one that understands the making of God’s kingdom as God’s own work. God is the builder, not us; rather, we are called to carry out our task, which is the task of grafting ourselves onto the story of Christ and his Church, as seen in the Gospels. In faith, we perform the tasks of charity, knowing God will shape such acts for the good.

And what form does that task take? Why, it is the form of Christ himself: a servant, humble, compassionate, merciful, abounding in grace, reveling in truth, rejoicing in the kinship of all of humanity. The work we are called to, in the greater task of God’s building of a nation, is to “love as God loves.” That’s it. It may not always be effective in the way the world counts effectiveness. But that was never really our goal, was it?

One final note: it can be easy to read this as an endorsement of political quietism, of a rapid withdrawal and disengagement in the world, and thus a kind of chosen ignorance about the injustices of this world as it is now. Simply claiming that it is God’s job to fix the world is the kind of political abdication practiced by so many toxic forms of mainstream, therapeutic pseudo-Christianity, right?

To understand the politics of charity in this way is to discount the potential embedded in the example of Christ to change the world. The example of Christ – the example of the peacemaker, of He who was willing to turn the other cheek and give of himself wastefully and to even die rather than wield power – is sufficient for the making of the world. It is the lie of the world to try to make us believe otherwise. We aren’t to become meek, humble, compassionate, loving and peaceful as a way of therapeutically avoiding the world’s suffering, as this lie would have us think. No, we are called to this imitation of Christ precisely so that we may more clearly see the suffering and injustice in the world around us, and then respond to it in a way that is truly effective, in the way effectiveness is counted by God. Will this always lead to a political, legislative, or activist victory? Not at all. But for Christians, our understanding of victory is counted on a different scale.

That brings us to the question of my next essay: what is the locus of our charitable politics in this world? Where and with whom do we practice putting on the story of Christ? The answer looks very shocking to a world dependent on – addicted to – the illusion of effective action and the wielding of power.