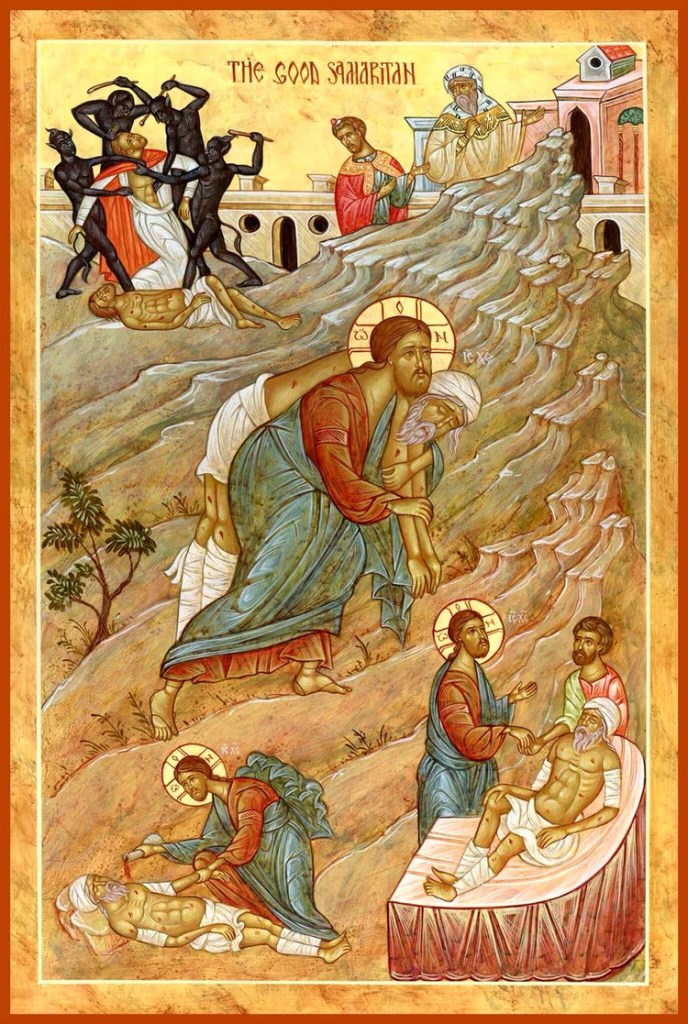

In the essay posted Friday, I described how Stanley Hauerwas brings Scripture to bear in our thinking about the effectiveness of Christian action, specifically the tales of the Good Samaritan, and Mary and Martha. The implications drawn from Hauerwas’ reading of the text are certainly shocking to any politically-minded Christian. He seemingly describes a Christianity bereft of any politics, or any interest in them, a focus that certainly would seem to confirm many of the worst fears many folks have about Hauerwas’ supposed sectarian and withdrawn theology.

Hauerwas is nothing if not self-aware, and anticipates this criticism well. In fact, his anticipation of this critique serves a crucial purpose in his essay, as he uses the accusations to turn the idea of Christian politics on its head. He writes,

It is my contention that rather how Christ forces us to be charitable requires the formation of communities that are fundamentally political. It is political in the sense that the church’s primary responsibility, her first political act, is to be herself.

This emphasis from Hauerwas is one we find throughout the breadth of his work as theologian. Time and time again he emphasizes an ontological difference between the world at large and the church. One of Hauerwas’s most well known – and most often misunderstood – statements is that “the first task of the church is not to make the world more just but to make the world the world.” Although many readers and critics interpret this as a call to separation and sectarianism, it is in fact Hauerwas’ mission statement for the task of the church in and for the world. He views these two kingdoms – or better yet, the two cities first envisioned by St. Augustine – as existing in a sort of symbiotic relationship. They both need one another. And at this point in this chapter, he really makes clear how the church can help the world know that it is the world – and how much it is in need of the church – or, more importantly, how much it is in need of Christ.

That need, of course, is tied up with the notion of charity. The church, as the “community of charity”, reveals to the world its own nature. By being a community bent not on having all the answers, but instead being with and for those in need, the church can remind the world of its own limits. But this won’t be an easy reckoning for the world, as shown so clearly on the Cross.

At this point, Hauerwas returns to Luke. As we saw in part two of this series, to understand the politics of charity, we must reread history, in order to see what part Christians have to play. I wrote then,

The work we are called to, in the greater task of God’s building of a nation, is to “love as God loves.” That’s it. It may not always be effective as the world counts effectiveness. But that was never really our goal.

And, as I noted at the time, this can be misinterpreted (and often is) as an endorsement of political disengagement, and in effect, silent acquiescence to the powers of the world. Hauerwas returns to that understanding here, seeing it at work even in the very text of Luke: “For one of the reasons that Luke wrote was to show that, even though Christ had been hung on the cross of political insurrection, Christianity was not subversive to the Roman Empire.” Luke, taking his cues from the Jews, was trying to make Christianity seem at the very least as not a danger to the Empire, if not as a good and quiet citizen.

And this is a good reading of Luke, not a dangerous one, “for Christ refused to take up the means of violence to secure a good and even charitable end.” Christ, in this sense, wasn’t a danger to Rome, not in the way the Zealots or many other violent revolutionaries and nationalists were. Jesus was never trying to overthrow the Romans or Herod and create a new political entity to rule in their place. Jesus wasn’t crucified because the authorities were worried he was about to overthrow their rule in Palestine. And Luke wants to emphasize that, because remember, Luke is writing to Roman citizens, trying to convince them that they can be citizens and also be followers of Christ.

But, Hauerwas points out to us that Jesus wasn’t harmless. The Romans still killed him. There must be something that Luke identifies as how Rome would justify his execution in this telling. They wouldn’t execute the leader of a popular movement without something compelling that reaction. So what was it? As Hauerwas points out, Jesus is just as politically and socially dangerous as armed revolutionaries, if not more so:

Rome was right to crucify Jesus and his followers, as they were far more subversive than the Zealots. Rome knew how to deal with Zealots, for the Zealots were willing to play the game by the rules set by Rome. Christianity was far more subversive, because it was constituted by a savior who defeated the powers by revealing their true powerlessness.

Jesus, through his eschewal of power and effectiveness, through his embrace of radical charity and love for those so often unloved, revealed the weakness at the heart of the state. Rome could only be in power as long as it could wield the fear of violence and death in order to keep people in order in a way that benefitted the great and wealthy. Jesus’ refusal to play that game, his willingness to embrace weakness, ineffectiveness, and powerlessness, in the service of those the state had long crushed, was an active danger to Rome. In Christ, the people saw the exposure of the powers and principalities and their weakness in the face of the real, authentic love of God.

“What the tyrant fears,” writes Hauerwas, “is those who insist that charity and humor is that which moves the world, for such virtues reveal the weakness of the tyrant’s power.” I love this line, and I think it is really the climax of his essay. It reveals a deep truth about human power, one that has been exploited again and again by fools and by those who refuse to play the game of the world. One of the characteristics of tyrants is their need to be taken seriously, for those around them and those they rule to acknowledge their power, their authority, their seriousness, their danger. As a result, those who would stand opposed to tyrants have weaponized humor, ridicule, and powerlessness in order to undermine those tyrants.

I started thinking about and writing this series when Donald Trump was still president, and I thought about his own very obvious and public need for people to take him seriously, how that primal drive was pushing him to take tyrannical action against those he perceived as his foes. And, I thought about how the most effective insurgents against him were not those who played the game by his rules, by punching back or tweeting or doing the things that reaffirmed his power over their lives. No, the most effective voices against the particular brand of Trumpian tyranny were the comics, the fools and those who refused to play his game. There is a reason – an important reason – Trump canceled the White House Correspondents Dinner, why his whole political excursion began after the Correspondents Dinner of 2014. There is a reason he particularly hated late night comics and Saturday Night Live. These various bodies and individuals weren’t just angry with him, as much as they just wanted to laugh at him. And if there is one thing a would-be tyrant can’t abide, it is being laughed at, instead of feared.

This same idea extends beyond individual tyrants, to the whole system of domination that the world is ruled by. The novelist and essayist Walter Kirn unpacked this in an essay, “The Holy Anarchy of Fun.” He writes,

Fun—when your rulers would rather you not have it, and when the agents of social programming insist on stirring nonstop apprehension over the current crisis and the next one, the better to keep you submissive and in suspense—is elementally subversive. Fun is ideologically neutral, advancing and empowering no cause. Fun is self-serving and without ambition. It wishes only to be. It produces nothing for the collective and may represent a withdrawal from the collective, temporarily at least. Your fun belongs to you alone.

Fun, the physical manifestation of humor, is a subversive pastime. Kirn again:

Fun is abandonment. “Don’t think. Do.” It’s a form of forgetting, of looseness and imbalance, which is why it can’t be planned and why it threatens those who plan things for us. Fun is minor chaos enjoyed in safety and most genuine when it comes as a surprise, when water from hidden nozzles hits your face or when the class hamster, that poor imprisoned creature, has finally had enough and flees its cage.

Fun is the alternative to the churn and drama of politics. The powers that be in the world don’t want us unplugged from the mess of politics and power. They don’t want us ignorant of what’s happening in the halls of power. Rather than being an alternative to the old saw of bread and circuses, politics has become the circus, and our outrage is the fuel that drives it. We channel that outrage and attention into dollars and clicks and shares, which is the oxygen the system needs to perpetuate itself and maintain control over us. This is why politics has been allowed to seep into every corner of the culture, from movies and books to food and art. Its power over us ensures the domination of the few over the many.

But, when we withdraw our attention and turn our outrage down and roll our eyes at the ridiculousness of the system and those enmeshed in it, we then find a truly dangerous freedom. We begin to live into a different kind of politics, one more concerned with the things that actually make up our lives- family, friends, the land around us, the decisions made in our neighborhood and our schools and our town. This is exactly what tyrants don’t want us to know. They want us fixated on the latest bullshit being spewed by whichever member of Congress most pisses us off. When we refuse – when we remember we are made for the Good, and that Good makes laughter erupt from deep within our soul, and we revel in it with good humor and fun – then, that is life. That fills us up. And we can pour it out on others, in charity and love and good humor. And those in charge, they can’t control or weaponize it, and thus become small and powerless and ridiculous. To reference the world of Harry Potter, the systems of power are just one giant Boggart: terrifying until we remember that power is an illusion, undone by laughter at its pretension.

The same dynamic was at play in Jesus’ ministry to the poor and the forgotten. His reminder that “Blessed are the meek” wasn’t as much a plan of political action, as it was a statement of ridicule, directed at the Powers of the world, a throwing down of the gauntlet to tell them, you may think strength is what God wants, but you would be wrong. Blessed are the meek. Blessed are the mournful. Blessed are the persecuted.

I am reminded as well of one of my favorite passages of Scripture, 1 Corinthians 1:25, where Paul writes, “For the foolishness of God is wiser than men, and the weakness of God is stronger than men.” Jesus didn’t base his ministry around showing how strong God was. No, Jesus’ ministry was about the meekness of God, and how that meekness, how the love and charity embodied in it, undermined the claims to effective power that the world depends on. Effectiveness isn’t getting things done. Effectiveness – God’s effectiveness – is just simply love, no matter what. It’s better politics, one that makes room for God’s kingdom. Oh, it certainly looks completely stupid and foolish to those without eyes to see and ears to hear. But it’s the only way to be the Church when they want us to be the World.