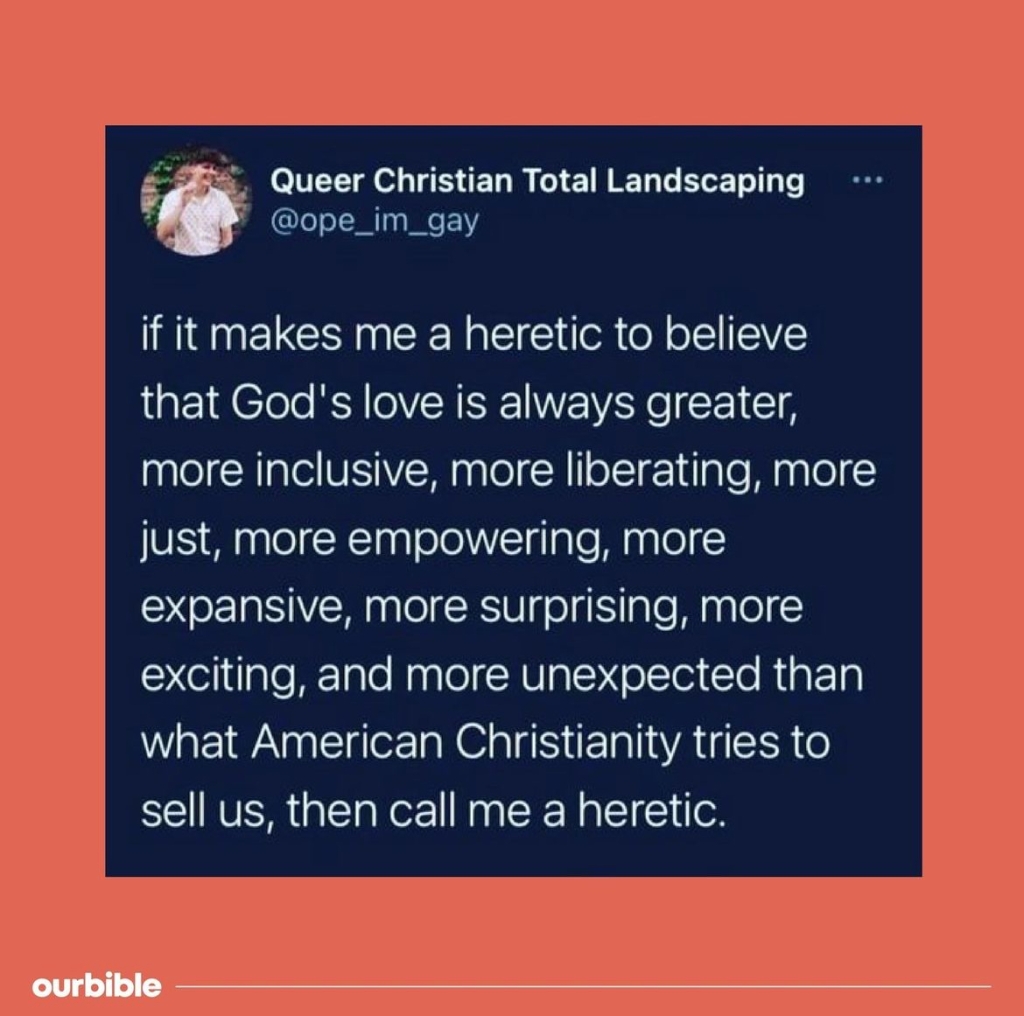

I shared this tweet in my Instagram story yesterday, and I got some interesting pushback from a handful of folks that I want to respond to.

Heresy is a word created by humans. It doesn’t occur in the Bible. People created the idea of heresy as a way to designate, in the long running theological battles over any number of issues, who is in and who is out. Its a human construct that serves a role in debates over orthodoxy. It is not a God-ordained marker about any particular belief.

So, when I share something like this, I’m saying that if someone wants to label me a heretic over a particular theological belief I hold, that I can live with that. The claim heretic is subjective; its someone’s opinion about a particular situation.

And frankly, when someone wants to wield the word heretic around the act of expanding our understanding of what God’s love encompasses, it really makes me want to turn that accusation around and throw it back. Because I truly, deeply believe that if you do or say or promote anything that tries to limit God’s love, that tries to put God in some kind of man-made box or make God smaller than God could be, that’s real heresy.

Here’s why I don’t think any of this is actually heresy, or wrong in any way. The Bible says, in 1 John, “God is love.” When we say that, we can only ever approximate the reality of love that is God with our language. We can’t really wrap our head, or our words, around the capacity or the depth or the magnitude of the kind of love that is God. So, to try to limit the reach of God’s love towards human beings – to say, this person is out for this reason – is to put a limit on God, is to stand in God’s place in making a determination about where God’s love does and does not reach. We are not here to make that call, as Paul reminds us. We are simply here to live into God’s cruciform love via our imitation of Christ, and leave it up to God to make any judgments.

Same goes for just how just God is (Deut 32:4), how liberating God is (Psalm 146), how unexpected God is (2 Peter 3), or how inclusive God is (Gal. 3:28). Our language cannot comprehend the attributes of God, it can only make vague gestures in that direction. So let us beware placing limits on the good things about God and God’s love for us and God’s desire for the world and for us. Always, always, always err in the direction of more love, more justice, more inclusion, more mercy. Always, in all things you do.

We should always remember that when Jesus tells us to do things like love our enemy, or to turn the other cheek, or to eat with tax collectors and sinners, or to judge not (all of which were deeply radical and countercultural statements in their context, something we forget because of their familiarity two thousand years later) it is always meant to challenge our comfort and our boundaries, and to remind us: this God we worship is boundless, is abundant, is wild. The only heretic is the one who tries to tame God.