The presidential election this year is undoubtedly, and unfortunately, a referendum of sorts on democracy in America.

This has been a common refrain from some of the shrillest voices on the left in America for the better part of eight years, and as someone who tries to avoid, as a rule, breathless, caught-up-in-the-moment political analysis, I’ve refused for the most part to take part in the panic. Every election becomes “the most consequential election in American history” to the average pundit or overly-engaged political junkie on social media. I feel like this shouldn’t need to be said, but if every election is the most consequential, then soon, none of them become overly consequential for the average voter, especially if they feel like they aren’t getting much in return for their vote. And listen, I get it. I was there in 2012. Beating Mitt Romney felt like a big deal. The stakes felt large. In some ways, they were. But not “our status as a liberal democracy is in danger” big. We shouldn’t forget that feeling, nor the feeling we have now.

I haven’t always succeeded, but I like to think I’ve been measured and calm, if reasonably alarmed. And, if nothing else, I’ve been clear from the start – you can read this essay from 2015 as proof of concept – that Donald Trump is a unique blight on American democratic norms and processes, not to mention our national conversation and character, and is manifestly unfit by dint of character and lack of intellectual curiosity to be added to the list of people who have held the American presidency. I found his first election repugnant and shocking, and he comported himself as president almost exactly how I expected him to: haphazardly, recklessly, with a lack of concern for the big picture, policy, or anything beyond his own narrow self interest and need to stroke his ego. His election was orders of magnitude different from past elections. Anyone who tries to act like he is somehow in continuity with the 43 people before him are either fooling themselves, lying, or have almost no concept of what past presidents acted like.

Trump’s rejection in 2020 was an important moment, and restored a bit of my hope in our democratic project. And then, like a bad rash, Trump came back, running again, and seemingly becoming the odds-on favorite to win, running a campaign centered on his desire for revenge and the anti-democratic hopes of a billionaire class married to right wing nationalism. It’s like a bad nightmare on repeat, only it’s a nightmare we all lived through once. Despite all this, I’ve tried to hold on to my political equilibrium, very consciously presenting an air of pseudo-indifference, some of that fed by my commitments as a Christian and the longer view of history that faith calls us to take.

But, here I am, less than a month before the election, and I’m ready to declare publicly – late, perhaps – that this election is a hinge point for American democracy, that the pundits and the partisans were correct, even if inadvertently: American democracy is under real threat of being dismantled if we elect Donald Trump to the presidency for a second time. Just like last time, his election is not normal, and we shouldn’t act like it. But, whereas last time he was qualitatively different due to his lack of fitness for office and his unique indifference to the gravity of the office he assumed, this time the difference concerns the nature of democracy and the future prospects of our experiment in self-government.

What changed? The shorthand answer is January 6th, and everything related to it that has come since. January 6, 2021 changed the terms of our national conversation in a way that our country probably hasn’t seen since the American Civil War. That sounds hyperbolic, I know, but let me make the case here. I think that references to January 6th in our political debated have become so rote to many that we are in danger of forgetting the magnitude of those events. Never before in the history of our country had something like that occurred. It was not a normal event, nor was it a mild one. Don’t remember it being that bad? Take a few minutes and watch a video of news coverage from that day. Watch what happened and refresh your memory on it. The images are still shocking. Don’t let the natural passage of time or the downplaying by Trump wash away the absolute insanity of the fact that, in America, in 2021, an actual mob of people broke into the United States Capitol building in an attempt to block the process by which our democracy transfers power as directed by the will of the American people at the ballot. This was not normal.

Leading up to the certification of electors, Donald Trump and his allies had been laying the groundwork for the events that happened, by their continued refusal to acknowledge the reality that Trump did in fact lose the election, not narrowly, but in fact quite decisively. They refused to accept this reality, and encouraged their most ardent supporters to act upon this belief. No, they may have not laid out an explicit plan of action for January 6th. But it beggars’ belief to claim shock and disbelief at the events of that day when the message they had been pushing all along had been, “this election was stolen, America itself is under attack, we must do something about this.”

Shock and disbelief are in fact the correct responses to the events of the day, for those of us who watched on. I remember watching the coverage that day in my living room, and being in a state of shock over what I was seeing. A mob of people – some armed – marched from the White House to the Capitol – not an inconsequential distance! – and proceeded to break into the center of our democracy by force, occupying one of the chambers of our legislature and generally running rampage through the building. Legislators on all sides were forced to flee. Police and security were assaulted. Someone died that day. None of these things is normal, or deserving of a shrug. The events of the day do not require a concise statement of revolutionary intent to be understood as a loosely organized but quite dangerous attempted coup aimed at the peaceful transfer of power in our government, something that had occurred every four years for the entire history of our democracy. And all of this was encouraged, supported, and promoted by Donald Trump, who now, four years later, wants to again take charge of a democracy he clearly does not believe in or care for.

In fact, that illustrates another terrible aspect of January 6th and the aftermath. It would be one thing if Donald Trump and his enablers triggered the events of that day, and then after it got away from them, began expressing the appropriate amount of shock and disbelief it required/ But shock and disbelief is not the attitude Trump et al. took – and continue to take – towards January 6th. Instead, as with anything Trump is asked to take responsibility for, it has been minimized, mocked, weaponized, and downplayed. So many of us shrug our shoulders at January 6th almost four years later because fully half of our entire political structure has decided to do so in pursuit of power.

This is the difference January 6th makes for me: beyond just the absolutely shocking nature of that day in and of itself, the way that it has illustrated Donald Trump’s deeply-ingrained inability to admit defeat or wrong, ever, in any circumstance, has made even more clear his unfitness for office, and indeed, his danger to the American democratic project as a whole. Donald Trump places himself, and his need for power and affirmation, above our country, and that which has long set our nation apart in the world, namely, our commitment to liberal democracy and constitutional governance. This should be a deal-killer for anyone considering voting for Donald Trump, especially for those who spend so much time telling us how much they love our country and waving the flag and printing the Constitution in their Bibles.

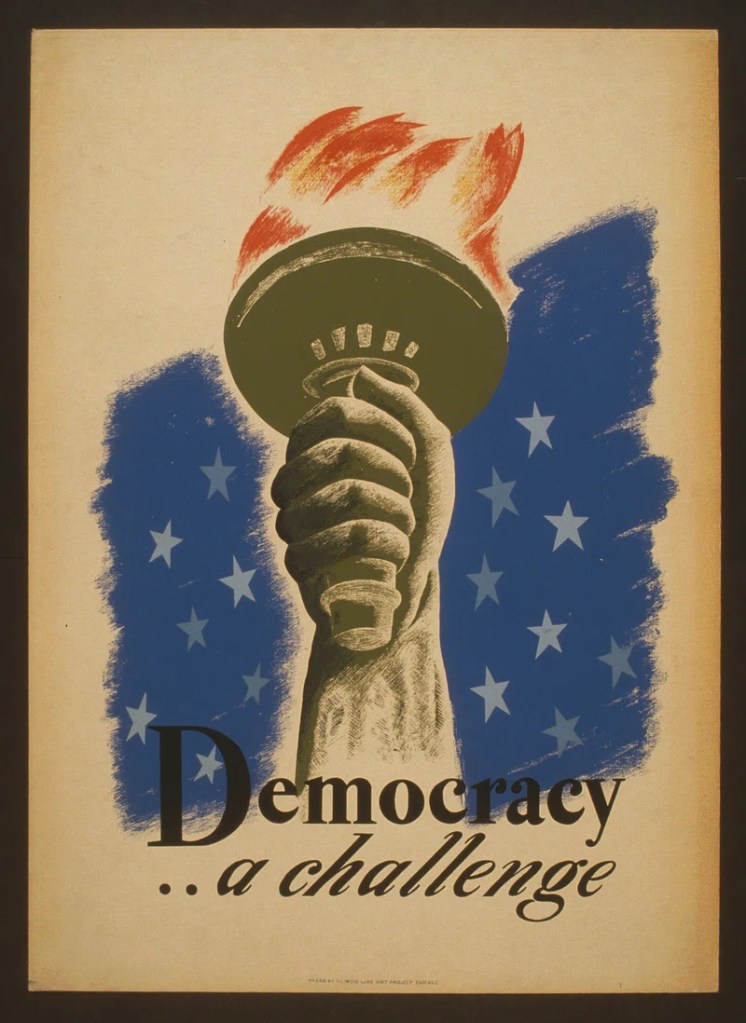

Our identity as a democracy is so important to our nation – more so than any other defining characteristic of America. To be a small-d democrat is core to what it means to be an American, rather than skin color, ethnicity, religion, or clan. This is what originally set America apart in the world of nation-states, and it is a heritage that should continue to motivate and animate our impulses and our self-governance.

And in a democracy, few things matter more than norms. Because democracy is, by its nature, a voluntary and participatory form of governance, it rests upon popularly accepted and venerated norms as the source of the kind of legitimacy found in predictability and regularity. These norms, in short, keep democracy working for everyone. Norms like respectful debate, trust in democratic institutions, truth-telling, transparency, and graceful acquiescence in defeat, whether electoral or legislative – all these things are essential to the proper functioning of the democratic structures delineated in the Constitution.

Donald Trump has actively worked to undermine and disrespect each of these norms. He is manifestly incapable of respectful debate and disagreement. He views all disagreement as personal attack, and responds accordingly. In a democracy, this is toxic. Respectful disagreement is at the core of our legislative process; it depends not upon unanimity, but instead upon the presence of debate, as a sort of refining fire that, in the best cases, pushes us towards a workable consensus. Trump is clearly incapable of understanding this concept, or of the idea that defeating one’s foe does not mean destroying them in all ways. His refusal to do anything but attack, name call, degrade, and lie about his opponents tears at the fabric of a participatory democracy.

Our democratic process also relies on democratic institutions to enact and protect our rights and the legislative decisions of our elected leaders. These institutions include first and foremost a stable and independent judiciary, a competent and informed executive bureaucracy, an unbiased and limited law enforcement apparatus, a free and uncensored press, and an informed, representative, and expansive citizenry. Donald Trump and his supporters have worked to undermine each and everyone of these institutions, both rhetorically and through their actions: through stacking courts with ideological partisans, through an attempt to politicize the civil service, through the manipulation of investigations and the use of organizations like the FBI to attack political opponents, through the constant undermining and attacking of independent media voices, and through extensive efforts to disenfranchise voters who they deem as less than sufficiently dedicated to them. All the while, they attack and spread numerous lies about all these institutions, and about the dedicated and honest American citizens who do the day-to-day work of each.

The norm of transparency is closely related to that of truth-telling, and serves a similar function. If we and our elected leaders are going to engage in the work of self-government, we must be able to see the world around us, to know what is happening, and to be made aware of the debates and ideas being discussed. We must know where the money comes from, and where it is going. Sunlight, as they say, is the best disinfectant, and if we value our ability to self-govern, we must be able to know who or what is influencing the process. Again, Donald Trump has shown himself to be completely opposed to transparency. He is the first major party candidate in the modern era to refuse to reveal his tax returns or his medical report, essentially refusing to take part fully in the job hiring process that is an election, thumbing his nose all the while at his prospective employers – the American people.

This touches on the next norm, that of truth-telling, which is in some sense the most important to a properly functioning democracy. If we and our leaders are going to debate and decide on important questions of policy and governance, we have to be able to do so from a place of truth about what it is we are discussing. Donald Trump is manifestly unable to speak the truth, in almost all situations and about almost all topics. We have become numb to his constant lying, because the depth and breadth of it is so staggering. But we cannot allow ourselves to be bowled over by it. The speaking of truths is crucial to our democratic project, and beyond that, to our freedoms. As the great philosopher Hannah Arendt said in 1974:

“If everybody always lies to you, the consequence is not that you believe the lies, but rather that nobody believes anything any longer…And a people that no longer can believe anything cannot make up its mind. It is deprived not only of its capacity to act but also of its capacity to think and to judge.”

Democracy rests most crucially on truth; it cannot function otherwise. The election of such a serial liar to the highest office in the land is a severe blow to democracy. Donald Trump does not engage in the small-bore lying and obfuscating common to politicians in all times and all places. No, Trump’s brand of lying is pervasive and overwhelming. Most liars rely on a subtle twisting or eliding of the truth to present their own version of a story; Trump is beyond this. He is what philosopher Harry Frankfurt termed a “bullshitter” – someone who “ignores these demands [of truth and lies] altogether. He does not reject the authority of the truth, as the liar does, and oppose himself to it. He pays not attention to it at all. By virtue of this, bullshit is a greater enemy of the truth than lies are.” Truth plays no role in his lies; only his vision of reality matters, and convincing others to disbelieve their own eyes and ears in favor of his. Such an act is an abdication of our own freedom and agency, and a fatal strike at the heart of democratic deliberation.

Democracy is an inherently hopeful and optimistic process. It requires a belief that there is a future worth planning for, fighting for, dreaming about. This is why fear-mongering and doom-casting are toxic to democracy. But, I’ll be the first to admit, we live in times where it seems like hope is hard to identify or feel. The rise of digital technology, the specter of geopolitical chaos, the continued economic tightening we all feel in our lives, the growing chasm of inequality and the glamorous lives of the elites that seems totally disconnected from the daily struggles the rest of us experience: I feel all these things too.

This understanding helps me see what it is, abstractly, that has powered the rise of Donald Trump. Our political processes have seemed indifferent at best for the better part of thirty years. Any progress has been fleeting, and it seems like we can’t even agree on the day of the week. Our leaders have manipulated our political system to a point where they are seemingly more incentivized to delay and obstruct the other side than they are to do the work of the people. So, the prospect of an outsider who is going to come in, bang some heads, blow some things up, and ultimately, make things work, is very intriguing. Don’t think I don’t get that. I do.

But Donald Trump is not that thing. He is not that thing because, first, the revival of our democracy requires a revitalization of those norms we just discussed, and second, it requires a hopeful and joyous outlook that he is uninterested in. Trump spends the majority of his time talking about all the people he dislikes, about who to blame, about how scary the world is and how fearful we should be. This is antithetical to a democratic ethos. A good future cannot be built upon a foundation of fear and scapegoating.

In his important book, Democracy and Tradition, philosopher of religion Jeffrey Stout writes of the importance of hope in democracy:

Democratic hope…is the hope of making a difference for the better by democratic means. The question of hope is whether a difference can be made, not whether progress is being made or whether human beings will work it all out in the end. You are still making a difference when you are engaged in a successful holding action against forces that are conspiring to make things worse than they are. You are even making a difference when your actions simply keep things from worsening to the extent they would have worsened if you had not acted. The failure to achieve progress, though common enough in democratic experience, should not be allowed to sap democratic aspiration altogether. There is still a beneficial role for democratic efforts even in regressive eras, if only a difference can be made.

Donald Trump is not interested in making a difference for the better, whether by democratic means or otherwise. The Trump movement is anti-democratic and unhopeful because of its call to blow everything up. Democratic hope does not destroy, but works to make a difference where it can, even in the face of defeat. A rejection of Trump is necessary, because what he will unleash will not be a different form of democracy that liberals and progressives don’t like and conservatives do, but because what he will unleash is an end to democracy. You can know this because of his reliance on fear and anger, rather than hopeful aspirations found in the joy of the difference we can make today. Democracy requires the hope for a better tomorrow. Donald Trump is incapable of envisioning a better tomorrow; the future he talks about instead rests upon scapegoating and demonizing other members of our collective democratic body. Such words and actions do not make a democracy, but instead fatally undermine it.

Every election can feel monumental and decisive in the moment. I admit feeling that way myself, as I noted at the start of this essay. So, I understand honest conservatives who strongly oppose the policy positions of Kamala Harris and the Democratic Party who feel like they have a duty to defeat her this year. I really do. But this essay is my plea: you must take a longer view of American democracy than simply this election cycle. No policy outcome that would be enacted by a Harris Administration is more important than the future of our democracy. Donald Trump is not another regular candidate, albeit one who is maybe a little cruder than others. He is qualitatively different from what has come before, and in a way that is a danger to what America should be. All critiques of Kamala Harris must pale before the threat to our democratic character represented by Donald Trump.

So, take a longer view. Recognize that a vote against Donald Trump does not come with a requirement that you then subsequently support all the things the Harris Administration might do. It does not lock you into voting her a compliant Congress two years from now. It does not require you to vote for her again in 2028. With the rejection of Trump, all those democratic options will remain open to us as a people. With his elevation to office again, that becomes much less of a guarantee. The question becomes, are you willing to risk democracy for the sake of whatever it is you think Donald Trump is promising you? Can you articulate that promise clearly? Is whatever it is more important than democracy? You cannot fix what you perceive to be wrong with our trajectory in one fell swoop, as Donald Trump wants you to believe. Sometimes, two steps forward are proceeded by one step back. Be willing to take that step back, while possessing that democratic hope of the two steps to come.

I’ve been very clear over the last eight years about my skepticism of and disgust about the direction of the Democratic Party in the post-Obama era. I stand by those things. I still have skepticism and distrust. Kamala is far from my first choice. I have concerns about the direction of her administration, especially on foreign policy and economic issues. I also just have a general aversion to the celebritification of American political figures; I refuse to be a fanboy for anyone. I say all of that to say, I hope I’ve earned a little bit of credibility of this topic. I am far from a hardened Democratic partisan.

What I am is a small-d democrat. I believe in democracy, and I think the democratic aspirations of the Constitution, the Declaration of Independence, and the Federalist Papers are the best way we could govern ourselves. It’s not perfect, clearly. But it is worth preserving, and fighting for. Democracy, far from Churchill’s least good option, is actually a good and virtuous thing, and we should want to preserve it. Generally, despite any policy differences, both Democrats and Republicans want to do just that. Donald Trump has shown that he does not.

This is not a full-throated endorsement of Kamala Harris. It is, instead, a strident and impassioned repudiation of Donald Trump, an endorsement of doing whatever we must – within the bounds of our democratic processes – to defeat Donald Trump and eradicate his anti-democratic, anti-liberal movement from our body politic. This may be our last chance.